|

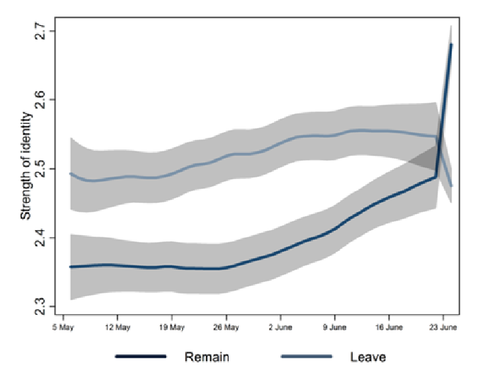

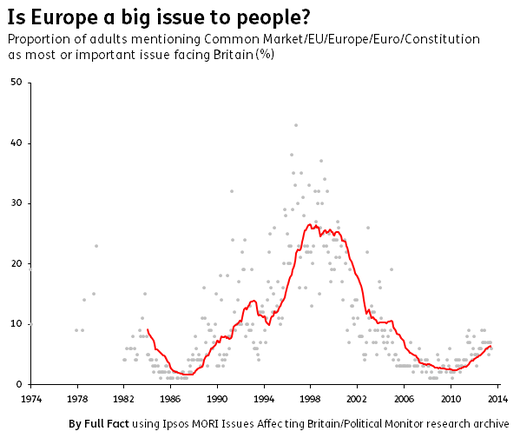

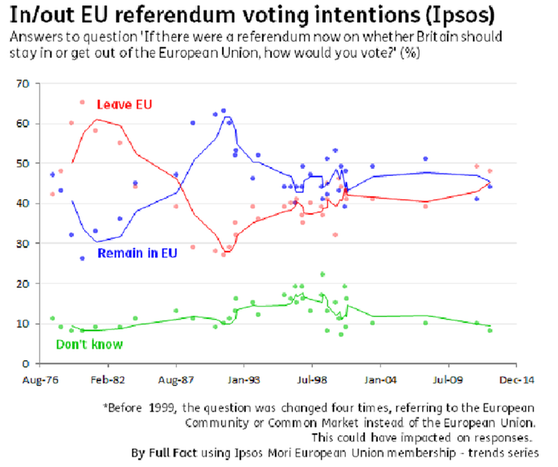

Can it really be only a year since we voted for Brexit? It seems so much longer. One cannot any longer mentally take oneself back to the time before, when we were accustomed to being in the EU and didn't for one moment believe we could really ever be so stupid as to vote to leave. It's the same about the 2008 crash; one can't really believe now that there was a time when the only question was just how fast pubic services and benefits should grow, and which should grow fastest. How on earth did we come to this? I've been thinking about it since offering myself as a subject to an academic who is exploring just that question: how did individuals assume the positions they now have, Remain or Leave? Particularly since in the years just before the Referendum, it's pretty clear that most us, whether pro or anti EU, simply didn't care that much. In 2014, when what were the most important issues facing the country, just 4 % spontaneously mentioned the EU. It wasn't even in the top ten concerns that people had (1). Of course, the UK's relationship with the EU (previously EEC) has always been fraught. Public opinion had been volatile, not to say skittish, over the decades. We joined in 1973 without a popular vote. Twice before Cameron, Prime Minsters riding a wave of popular antipathy towards the EU negotiated improved terms before securing approval for continued membership, including the previous referendum in 1975. In fact, public opinion was never so overwhelmingly anti EU as in Thatcher's early premiership - yet she was the one who ensured continued membership then, while Labour opposed it, facts 'forgotten' by both parties now. Chart 1: public concern about EU over time Chart 2 views on leaving/remaining over time But British views on the EU were always more complex and nuanced that the binary choice, Leave/Remain.. In the 2015 edition of 'British social attitudes', John Curtice, doyenne of British pollsters, showed that while usually only a minority had been consistently clear that they really wanted to Leave come what may, many Remainers also had reservations about the EU, and wanted reform (I came into this category myself, see my post of 31 May 2016 ) (2) . Few were ever unreservedly pro EU, or fully accepted it as it was. But at the same time, polls show that many who were unkeen on the EU did value some things about it: the protection of workers' rights, free trade with the EU and free movement of Brits into the EU (but as we will see, what many people seemingly meant was a one-way street). So the British seemed to have a majority for reluctant acceptance that being in the EU was better than not, weighing up costs and benefits. But what they really wanted was a reformed EU, re-made in a way that suit them better. Of course, there were different views on what 'reformed' meant – something not adequately explored by Cameron, who seemed happy to take whatever was offered him and present it to the UK public as significant change. Curtice also showed that the British thought about the EU in 2 different ways : instrumentally I.e. in times of practical benefits and results (stronger among the middle classes who benefited most) and in terms of identity, such as cultural cohesion and owning 'control'. There was a ready feeling, egged on by right wing media, that the EU was intruding excessively into things that ought to be for the UK to decide on. Britons felt they wanted to be 'in Europe but not run by Europe', a phrase which seems to capture the majority pre-Referendum mood. That is borne out by the regular survey of public opinion in each EU country (3), which has always placed the UK towards the Euro-sceptic end of the spectrum, but especially as regards the possible expansion of the EU's role (e.g. a European army, common foreign and defence policy, full economic and monetary union). Similarly, Britons never shared Blair's enthusiasm for the Euro (a fate Brown saved us from, and deserves more credit for doing so.) The issue of identity became linked particularity to worries about immigration, which rose enormously after the mid 1990s, first from outside the EU and then later in the mid 2000s from within the EU (I wonder how far the public ever really distinguished the two?). The UK was far from alone on this, indeed in EU surveys some other countries reported greater concern than us on the issue, and in no less than 20 countries it was reported as the top public concern in the EU survey in 2015. But the UK was shown consistently least supportive of free movement within the EU and most likely to see control of immigration as issue for national Government, not the EU. Within UK politics, immigration was, by far, identified as a key issue by voters by the middle of this decade. On this reading, the refugee crisis of 2015, including Merkel's dramatic pronouncement of a massive numbers of which every country 'must' take its share, and scenes of violent chaos on the borders, was tailor-made to drive the UK to vote Leave. (If, as has been suggested, Russia worked with Assad deliberately to drive a million refugees in Europe's direction, his strategy was brilliantly successful.)(4) The result of these concerns about identity was that UKIP, which had done remarkably poorly in the 2010 (only 3% of the vote), began to gain traction. It came first in the European Parliamentary elections in 2014, they got 17% in the simultaneous local elections, and 2 Tory MPs defected. Cameron, to stave off UKIP inroads into Tory votes, offered the Referendum, misreading the polls which in headline terms still seemed favourable to Leave, but not detecting the shift in underlying attitudes from instrumental issues to issues of identity, or believing he could negotiate real concessions on migration. But in the end he secured remarkably little change, and none of substance on the key issue, migration. This distinction played into the campaign itself. Leave understood that the issue was identity and especially immigration: hence the appalling Leavers' lie, that Goebbels would have admired, that a million Turks were on our way here to rape your wives and daughters (5) While Remain utterly failed to run the instrumental argument that being in the EU (including migration from as well as to the rest of the EU) had given us great benefits. Mandelson describes the decision by the the Remain campaign not to explain what the open market meant, and how greatly it benefited us (6).- Instead, relying on warnings of catastrophe, which were simply not believed. The effect of this bitterly divisive campaign was to destroy the more nuanced, balanced understanding that had existed, and force everyone into one side or the other of a strictly binary choice. It also seemed to rule out the possibility, however remote, of 'reform' some time in the future. This polarisation is shown in real time by analysis by the British Election Survey of how, during the campaign, people began with increasing strength to identify with the community of Leavers or Remainers – and continued to do so after the vote. What is striking is that while the Leave group was more strongly cohesive at the start, Remainers became more so towatds the end - and their cohesivness, their feeling of being part of a beleagured community, intensified remarkably in the shock of defeat. The democratic process iself drove us apart. Chart 3: increasing polarisation during the Referendum campaign, and after  That was been my own experience. Before the Referendum, I was pretty Eurosceptic, that is to say, while I never really wanted to leave, I was aware of how dysfunctional the EU was (and is) and how incapable of reform. But the moment we were asked to vote whether we really, seriously wanted to leave, I had no doubt that leaving must mean a huge and permanent loss of wealth, and of influence in Europe and beyond. But more than that, it means mentally turning our backs on the world and turning back to the past.

The Campaign itself solidified my views. I met many Europeans while canvassing in Oxford, a great international city, and though how much I liked having them around, how much I had in common with them as they wished us luck; I met ardent Leavers whose reactionary values, contempt for foreigners, credulity for blatant lies and sheer wilful ignorance I found repugnant. At national level, too, the lies, hate-filled nationalism and outright racism of the Leave campaign appalled me. So I started by thinking instrumentally, but ended up putting more weight on identity: only my identity turned out not to be nationality. So that was what happened: a majority for a sceptical, nuanced , pragmatic acceptance of the EU was over- turned by botched handling of immigration by the EU, failure by Cameron to secure signifiant reform, by a vicious, xenophobic and racist campaign, and by the very nature of the Referendum itself, which forced us to take one side or the other, forced us all into our trenches, which we began to dig and reinforce against attack. And now the British people are terribly divided: polls show that remarkably few have changed their view since the vote, we comfort and support 'our' people in 'our' side and stare at the enemy lines through periscopes across 'no-mans land', which is where we used to live. The enemy is ourselves. Not the least poisonous aspect of this is the excruciatingly slow pace. If Brexit had been over and done within months, we might now be on our way to adjusting to it. But it moves glacier like. It will be years and year before we fully leave. And then years before we fully see and understand the consequences, economic, geopolitical, cultural, psychological, social. And in the meantime, all we will hear about, all we think about, is Brexit, Brexit, Brexit. Parliament itself is devoting the best part of 2 years to nothing but. And every twist and turn of the process injects remains us how right we are, how wrong they are. It This process will take the rest of my life. I will die to the tune of Brexit. So let us now all agree to curse the man who is principally to blame for this: David Cameron. Is there, in all our history, a Prime Minister who has done greater harm to this country? The man who played Russian roulette with this country's prosperity, influence and sense of community, for personal and party political advantage. And lost. The man who fired the first shot in the civil war that propelled us into our trenches. And is he now contrite? Well, here's what he had to say recently: “Obviously I regret the personal consequences for me. I loved being prime minister. I thought I was doing a reasonable job, But I think it was the right thing. The lack of a referendum was poisoning British politics and so I put that right.” (1) https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/economistipsos-mori-september-2014-issues-index?language_content_entity=en-uk (2) http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/media/38972/bsa32_fullreport.pdf (3) http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm (4) https://www.theguardian.com/media/2017/jun/29/where-is-the-space-in-the-guardian-for-traditional-values (5) http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/nigel-farage-turkey-brexit-eu-referendum_uk_57234a8ae4b0d6f7bed5d801 also http://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/661387/Migrant-crisis-Nigel-Farage-Turkey-EU-visa-free-travel (6) See my post of 6.7.2016

0 Comments

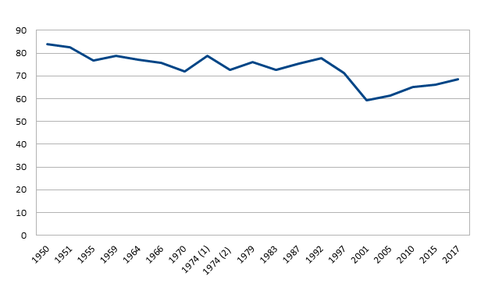

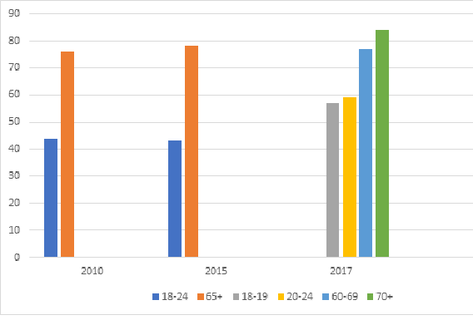

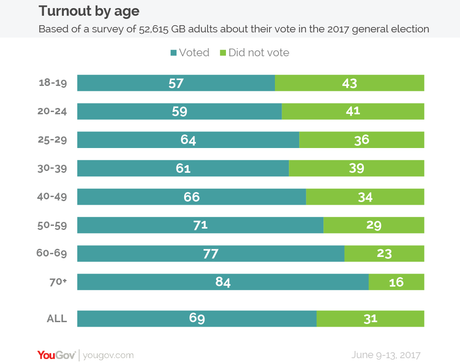

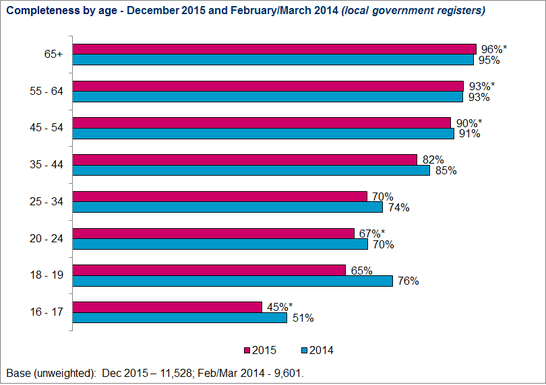

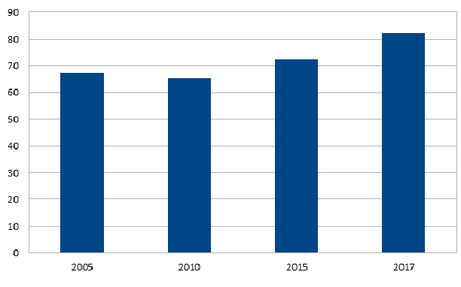

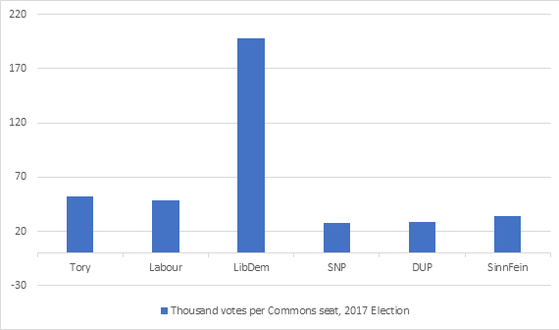

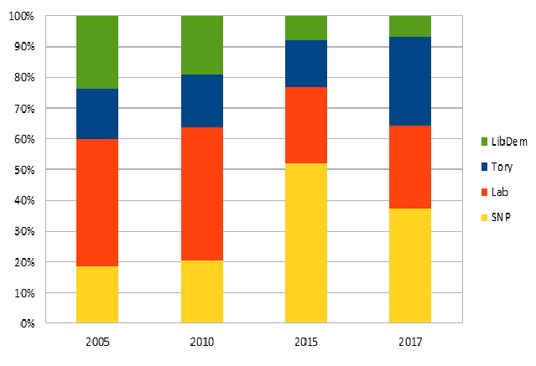

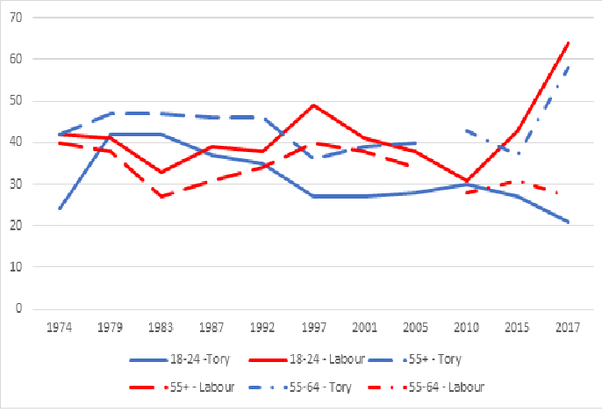

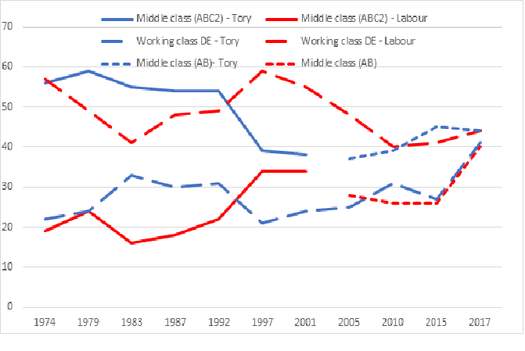

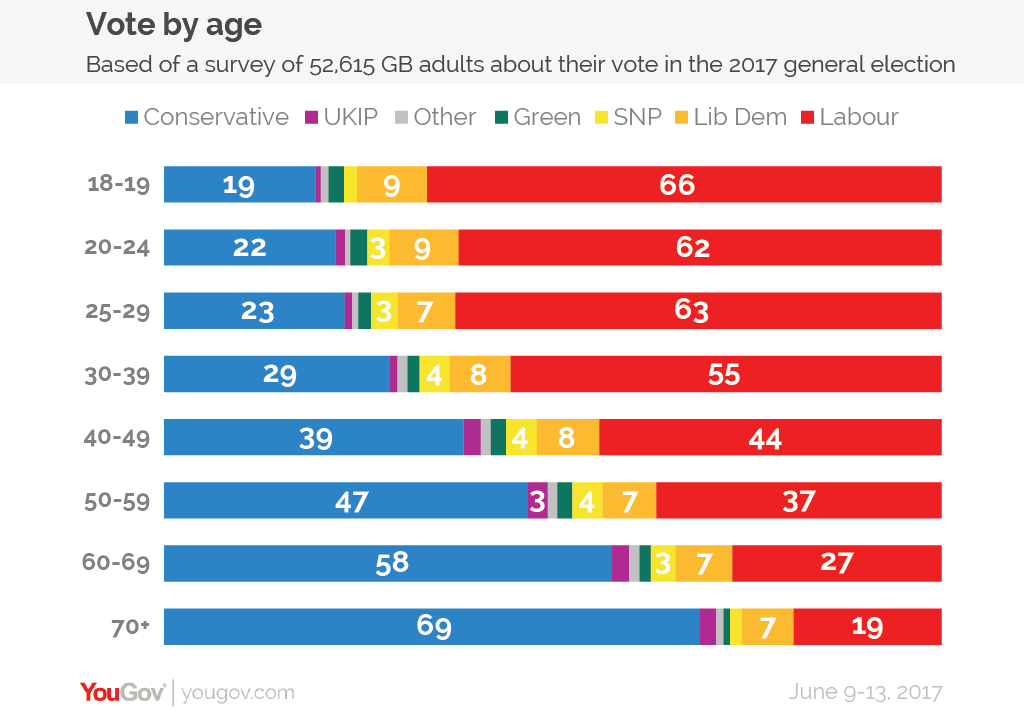

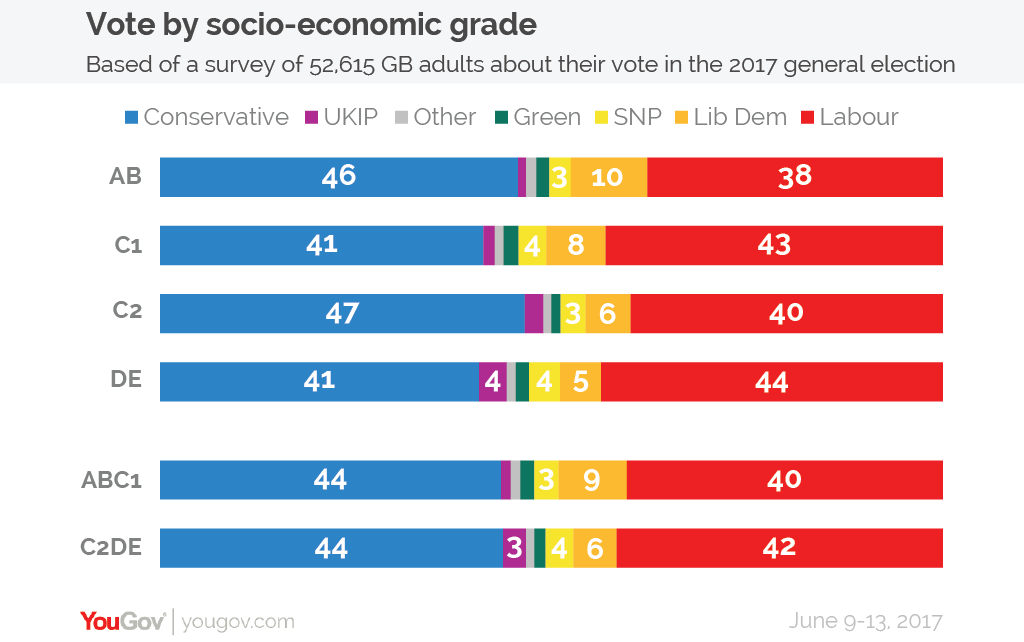

We now have the first good data on the pattern of voting in the recent Election, that is, based on a representative sample interviews conducted after the Election (from YouGov). (Earlier figures had been estimates based on pre-Election voting intentions, or on correlations between voting patterns an demographics in each constituency.) The data suggests big changes in the behaviour of the electorate which the Tories should be very worried about, but there is unpleasant news for Labour too. Here are the main themes as they strike me. The British are becoming more engaged with politics – chart 1 Turn out has been rising since 2005 – though is still way below what is what in the last century. (By the by, isn't it curious that the historic collapse of turnout occurred under Tony Blair, the great communicator?) Chart 1: long term trend in % turnout Source: http://www.ukpolitical.info/index.htm The young have woken up – some of them – charts 2 and 3 It has been a dependable truth in politics that the young don't register and don't vote, while the old do both. That was certainly true in the in the 2015 Election. (There is some evidence that turnout was higher for the Referendum. (Note 1)) That may be changing. Nearly twice as many 18-24 year olds registered in the run up to this Election, compared to the same period before the 2015 Election. For the first time in a General Election, so far as I can establish, a majority of young people who are registered actually bothered to vote. (But turnout was slightly higher for the old, too.) Chart 2: trend in % turnout of young and old groups But even now, the young are still nowhere near as engaged as the old. Chart 3: turnout by age, 2017 Election (from YouGov report) Forget that line about the old stealing the future from the young; the young gave it away. I can't do the modelling, but it looks likely that if the young had matched the oldest on registration and turnout, Remain might well have won and Corbyn might well be in No.10. But still, 6 million Britons exlude themselves from our democracy - chart 4 The latest estimates for electoral registration date back to 2015, when research by the Electoral Commission suggested that some 15% of those eligible to register do not do so. That overall figure has changed little since previous estimates, but within the total, there have been significant falls in registration by the young, by private renters v home owners, and by those who move frequently. Registration rates, like turnout rates, increase with age. Chart 4: estimates of changes registration rates by age (from Electoral Commission) These falls were associated with the move from whole household registration to individual registration in 2014. Was the move to individual registration a cunning plan by evil Tories to crush the young and exclude them from power, as the Left now seem to believe? Hardly: Labour introduced it in Northern Ireland, and the Electoral Commission had pressed hard for it to be adopted across the UK. And it was the right thing to do. Allowing the head of the household to register everyone living there harked back to an earlier, patriarchal age, and was open to fraud. 18 year olds are adults - and should be treated as such, not as children. At the same time, registration has become infinitely easier, and quicker: it takes about 3 minutes online (when campaigning on the Referendum, we were able to register people right there and then on the street). There are frequent public campaigns to tell people how to register. One might think that if people cant be bothered, they deserve to be excluded from political participation. And some might have their own perhaps nefarious reasons for not wanting to be on the register. One the other hand, it isn't a healthy democracy where 1 in 7 people exclude themselves, bearing in mind that of the remaining 6, 2 are registered but then don't vote. Specifically, it is damaging to our society, and leads to distortion in policy making, that the young are so under-represented. There is a case for making up-to-date registration mandatory (rather than voting – which doesn't seem to work well in other countries), for example, if you want to claim benefit or a bank account or a driving licence or bank card or insurance, you have to be registered at that address. Two party politics is back - charts 5 and 6 The proportion of votes cast for the two big parties is back up again, reflecting the collapse of UKIP and the fall in SNP, LibDem and Green votes. Chart 5: % of votes cast for Labour + Tories One consequence is that the 'disproportionality' of the vote - the extent to which different votes were over and under represented in terms of seats - measured by something called the Gallagher Index - was lower than it has been for a long time (Note 2). This is because in a First Past the Post system, the more votes there are for smaller parties, the more 'disproportional' the results. It's still pretty disproportional, of course: Chart 6: seats required per Commons seat, by party, 2017 Makes one think, when the DUP hold the balance of power! Multi party politics is back in Scotland - chart 7 The threat of a perpetual SNP monopoly of power in Scotland has receded. Chart 7: trend in distribution of votes between parties in Scotland (But for Labour and LibDems, little revival in terms of vote share: rather, the story is of a break-through by the Tories. Perhaps because the Scottish Tories have demonstrated clearly that they arent content to be simply the Edinburgh office of a London based conglomerate, perhaps because they are so clearly opposed to another independence vote, which seems remarkably unpopular in Scotland now, just as a 2nd EU referendum is unpopular here.) Age has replaced class as the dividing line in UK politics - charts 8-11 This is the most interesting part. Until this election, the main dividing line between Labour and Tories was class. Chart 8: trend in % votes cast for Tory and Labour parties, by age, 1974 on (data from Ipsos Mori) Note: Ipsos Mori changed their definition of age groups in 2010, hence the break in series, but the trend is clear. And is even more pronounced if one uses the over 64s in later years. Chart 9: trend in % votes cast for Tory and Labour parties, by class, 1974 on (data from Ipsos Mori) Note: again, the definition of class changed in 2005, so again a break in series. There should be a special circle in Hell reserved for statisticians who repeatedly break a series without doing the data on both bases for at least one year. The middle class had a brief fling with Labour under Blair – as we know – but in 2010 and 2015 seemed to return to their usual strong bias towards the Tories. While the working class was loyal to Labour. Meanwhile on age, there had (incredible though it may seem) never been a consistent correlation between youth and voting Labour. The young moved to Labour under Blair but in 2010 were again evenly split Tory/Labour. The old by contrast had indeed always been more Tory but often by only a small margin – and they too swung to Blair (was there any group immune to his charm?) But now look at the full 2017 results (switching to YouGov here since their data appear to be based on post Election interviews, not exit polls or pre Election intention to vote polling). Charts 10 and 11: voting by age, and by class, 2017 (YouGov) Class seems no longer matter. What matters now is age: the young are overwhelmingly Labour, the old overwhelmingly Tory. The age gradient is steady: YouGov calculate that for every 10 years extra age, the Tory lead increased by 9 points. The crossover – where Tory voters start to outweigh Labour – is now 47.

47! That figure should terrify Tory strategists . The young are lost to them. (Of course it is possible that as the current young age, they will turn rightwards; but then new first time voters will also one assumes be overwhelmingly Labour.) An additional factor is that Labour was so imaginative this time with its use of social media – the Tories barely compete. The Mail and Express preach to the converted. True, one election does not confirm a trend. It may all look different next time (just as the Blair boom for Labour among the middle classes and young faded by 2010). And it's true that the British public just now are nothing if not changeable. But the figures are so strikingly different to anything that has gone before that one senses the change may be a continuing one. It is also consistent with brutal economic and political realities. As the Intergenerational Foundation has charted, the past decade has seen a huge switch in the balance of present and future wealth from young to old: student debt, unaffordable housing, pensions, you name it (note 3). It has also seen a historic decision of unprecdented importance, Brexit, won by the old against the wishes of the young, nostalgia and reaction trumping hope and opportunity. The young should be seething. The influence of the Referendum Might this sea change may be in part a side effect of the Referendum campaign? Because it was not fought on party grounds, and both main parties were split on the issue, it may have served to 'un-moor' voters from traditional loyalties. The Referendum also pitted the backward looking against the future minded, age v youth. But what does it mean? One can go on analysing the vote in terms of this and that social group, area, Leave v Remain and so on. But to me, the result had a more general meaning. It feels like the nation is struggling to say something, perhaps something like this: “You politicians, you've have done your best to divide us, and you've succeded brilliantly. We're are now more divided than ever, and you'll find that makes us difficult to govern, just as we face the perils of Brexit and terrorism, and the challenges of low growth, an aging population, and heavy debt. How will you bring us back together, so that we can face the future positively?" To do that, we need leaders of exceptional vision, generosity and humility. But all I see are 3rd and 4th raters, mouthing out-dated and failed ideologies, looking to short term personal and party advantage, placemen, mountebanks, liars and of course, the great buffoon, serial liar, cynic, cheat and racist lout who hopes to be our next PM. Only one MP, perhaps, springs to mind, who might have developed into the sort of politician we now need: Jo Cox. NOTES 1) see: http://www.ecrep.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Did-young-people-bother-to-vote-in-the-EU-referendum.docx 2) The index involves taking the square root of half the sum of the squares of the difference between percent of vote. Since you ask. 3) http://www.if.org.uk/the-issue/ |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed