|

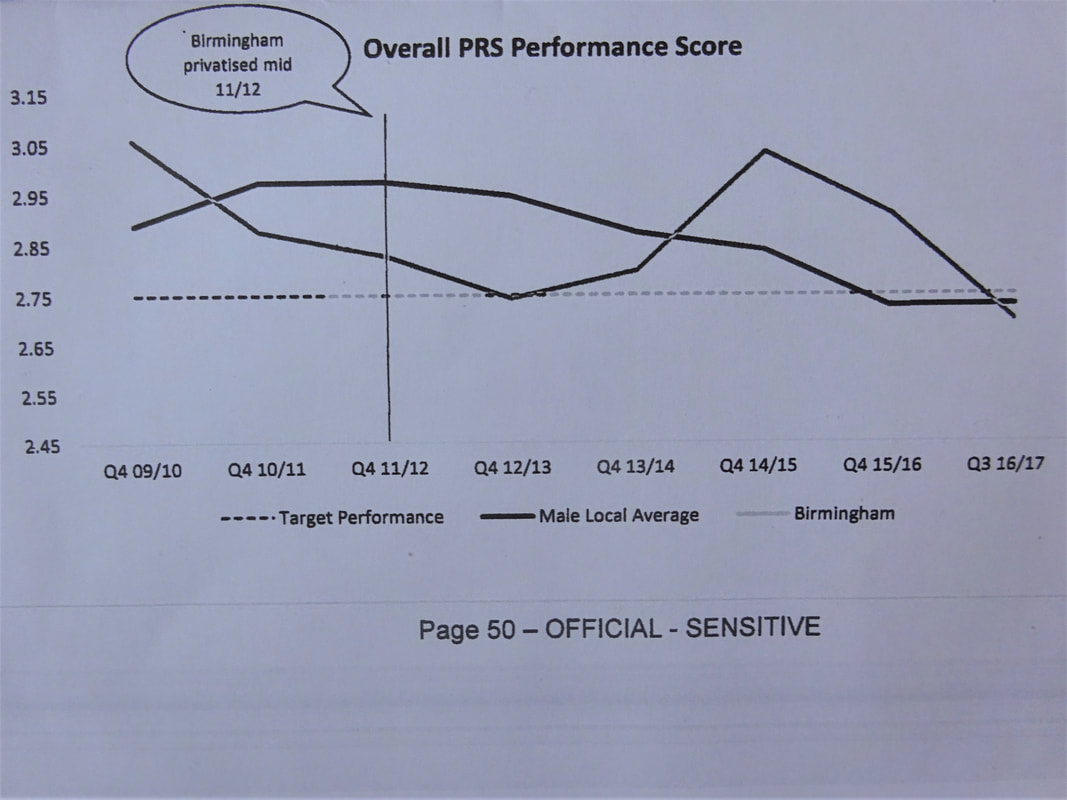

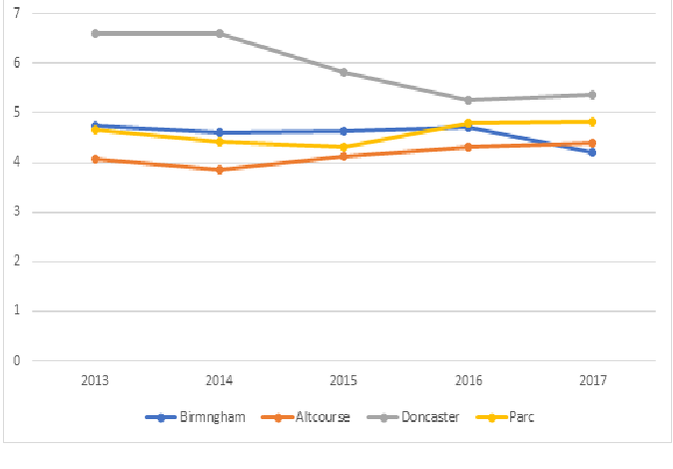

NOTE [added 1 September: I have received quite a few comments privately on this piece; I have summarised some of general interest at the end] I have been reading the report of the internal MoJ inquiry into the major riot at Birmingham prison on 16 December 2016, which had been withheld, but then released this week following a Freedom of Information Act application. It has been redacted, but not much. The report, by a former Director of what was then the National Offender Management Service (NOMS), is a most illuminating document, detailed, balanced, thoughtful. It not only casts light on how Birmingham prison reached the dire state described by the Chief Inspector in his Urgent Notification last week, but vividly illustrates perennial truths about how to run – and how not to run prisons – and what a difficult and important a job that is. Anyone seriously interested in prisons ought to find time to read it. It comprises first an analysis of what happened on the day of the riot, and second how the prison had deteriorated in the preceding 12 months, to the extent that staff had effectively already lost control well before the riot. I am not primarily interested in the actual riot, but the detailed, minute by minute account of the loss of control is as gripping as any film – quite terrifying. It sets the scene by describing how staff shortages and high turnover over many months placed staff, inadequately supported by management, under intolerable pressures and lead to disrupted regimes which in turn fueled prisoner boredom and discontent, and how staff gradually ceded control of the wings to prisoners. Then, on the day, an act of defiance by a couple of difficult prisoners gradually escalated, needlessly, as several opportunities to contain things and regain control were lost due to muddle and lack of grip by middle and senior management. Prisoners reacted to indecision by turning to violence, and soon even those who'd have preferred to stay out of it felt obliged to join in. But the report also records some acts of great courage by staff, in rescuing vulnerable prisoners from danger and holding vital control points despite ferocious assaults by groups of prisoners. One scene sticks in my mind: one wing had been lost, staff were running for safety, but one staff member saw a vulnerable prisoner who he knew would be severely beaten or worse, ran back at great risk to get him and they both then pelted down the wing for safety, closely pursued by a mob. 'The PCO described his good fortune at managing to unlock and secure the gate first time...' I bet he did, but not in those words! Once safe, the prisoner vomited with terror and relief and then would not leave the PCOs side. G4S failed abysmally - but some of their staff past the test alright. I do hope their courage and professionalism has been recognised. The second part of the report analysis how control was eroded over the preceding year or so and it is hugely illuminating. First of all it confirms what I have been saying, that the prison which improved markedly after transferring from public to private sector management in 2011. Two things confirm that. The first is research by Alison Liebling and others which showed improvements on 7 dimensions of prisoners' 'quality of life, as defined and measured by them: ‘respect/courtesy’; ‘humanity’; ‘decency’; ‘care for the vulnerable’; ‘staff-prisoner relationships’; ‘fairness’; and ‘personal autonomy’. Even more marked were improvements in the quality of staff life, including relationships with line and senior management – an extraordinary and important achievement, considering the feelings aroused by of the competition in 2011 and the highly contentious move of existing staff to the private sector, the first time this had ever happened and (as I know) long the source of much worry amongst policy makers (1). This progression is confirmed by NOMS own Prison Rating System, a sophisticated analysis of many aspects of prison operation, over the same period. I reproduce a graph, showing this improvement according to the PRS after privatisation in 2011, up to January 2015, and the precipitous decline thereafter. (Note the steady decline in public sector prisons right across this period). Chart 1: ratings of Birmingham and other local prisons, NOMS Prison Rating System Thus, two lessons immediately: 1) privatisation was not the issue (in fact, privatisation had initially lead to much improvement, albeit from the low level in which previous public operation had left the prison); and 2) the decline began way back - two and half years ago. The report doesn't help pinpoint quite why the prison started its rapid decline around January 2017 though there is some suggestion that the drug problem became much more serious around then, and it was just at that time that assault and self harm rates began to accelerate upwards across the whole system, so the cause or causes weren't peculiar to Birmingham. Staffing levels, and management of staff, are central issues. Mapping the data from this report onto data I previously obtained under FoI, budgeted staffing levels (302 PCOs) have not changed significantly since 2013, and probably not since privatsation in 2011. Neither budgeted staffing levels not the number of posts vacant (about 3%) were out of line with other prisons – on my analysis, the staff:prisoner ratio was considerably better than Doncaster or Thameside, and about the same as Parc. Chart2: Prisoners per PCOs at Birmingham and comparator contracted prisons Source: PQs and FoI applications Note: figures affected by reduced pop after 2016 riot But the staffing situation was nevertheless very difficult indeed – dangerous, in fact - for several interconnected reasons:

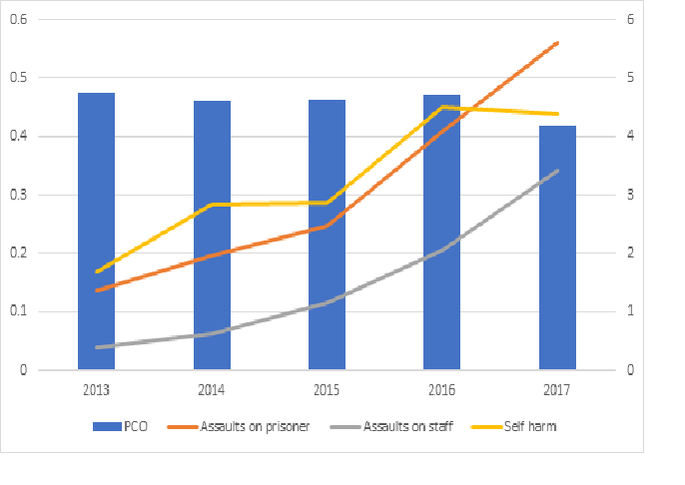

Thus the planned regime simply wasn't deliverable with available staff numbers. There weren't enough staff on landings, prison routines were constantly disrupted and many staff were new, insufficiently trained and scared. As we know from previous breakdowns in privately run jails (3), this quickly become a downward spiral - with new staff appalled at what they are faced with and choosing to quit or, if they stay, adopting passive and defensive behaviours rather than challenging misbehaving prisoners. Staff complained that they were poorly supported: 'new staff....reported feeling ignored and marginalised, and made to feel like a nuisance when they asked for help'. Management was suprisingly weak in many other ways. Managers insisted staff maintain a 'full regime' despite low staff availability - but it wasn't even clear to staff (or the inspectors) exactly what 'the regime' was supposed to be! Policy on unlocking was also unclear and staff seemed to make it up as they went along. The consequence of all this was a gradual retreat from authority, a process so familiar in prisons. Prisoners bullied and conditioned staff into unlocking everyone, whether entitled or not, and the IEP scheme, meant to relate privileges to behaviour, was hugely undermined. Unlocking everyone despite dangerously low staff availability became the norm, with staff unable to reconcile safe staffing minima with management's demand that they to keep prisoners unlocked (4). Staff over relied on prisoner volunteers to keep order, and some of these were not averse to using violence to do that job (and possibly some had other agendas of their own). The jail really had been turned over to prisoners to run! Extraordinarily, prisoners who wanted to be unlocked into this unsafe environment were asked to sign that they accepted the risks, an absolute abdication of responsibility by staff (and G4S). Staff seemed to loose control of such a basic thing as movement around the prison. Discipline was effectively abandoned - in one period only 1 in 6 serious assaults were referred to the police, of 655 cases so referred only 1 in 10 lead to a conviction. Violence went unpunished and drug taking went unchallenged. Vulnerable prisoners were not properly protected. Prisoners' attitudes in such circumstances varies – some relish the lack of control, but others find it threatening and difficult, finding they were unable get the help prisoners need from staff to get things done: “There as too much freedom,we like freedom but there weren't enough staff to deal with it. You weren't made to do anything, no discipline, no structure ...You couldn't find any staff...they let us get away with anything. Every day was a party. But boredom leads to badness”. “Boredom leads to badness” - that should be inscribed above the gate of every jail. The result was soaring rates of drug taking, self harm, and prisoner on prisoner and prisoner on staff violence. Chart 3: number of PCOs, assaults, self harm incidents at Birmingham, all per prisoner Note: PCOs on right hand axis, other data on left axis The management response was hopelessly inadequate. There are processes to ensure data such as assault and disciplinary rates are regularly reviewed in jails and that Governors/Directors regularly assess the stability of the jail. At Birmingham management assessed the jail in the weeks before the riot as 'low' i.e. 'there is no evidence of increased stability or instability above the norm'. That had been the rating throughout 2016, as every indicator turned glaringly red. The report suggests that management had been conditioned to accept very high levels of violence as the 'new normal'. In plain English, management had completely lost it.

And not only management. Each private prison has a number of MoJ officials – 'Controllers' – permanently working inside the jail to monitor operations. Here the report is more reticent, but it appears to confirms what a number of commentators have remarked on, a tendency of the Controllers to retreat into bureaucratic box ticking role. If they had walked the walk and talked to staff and prisoners, and taken a more common-sense over view of the state of the jail they could not have missed the seriousness of its rapid deterioration. But the role of Controller has always seemed unclear, and it's a difficult job to fill, because you need able experienced Governor grades, but such people would rather be off running their own jail. What does the report, on a riot 20 months ago, tell us about the run up to the Chief Inspectors extraordinary intervention last week? Difficult, because until the full report on this most recent inspection is published, we don't know what happened in those 20 months. But I think we can already say:

More general thoughts prompted by reading this extraordinary document:

COMMENTS RECEIVED

(1) In my time it was thought too risky to attempt without much reducing prisoner numbers during transition, something we never had space to do. (2) Rates this high were common in privately run prisons in the early 2000s and as recounted in my book, were key in bringing several to crisis point. Public sector rates were then very low – possibly too low. I had been told that changes in the labour market after the 2008 Crash had brought rates right down, to 10% or so: but clearly, not everywhere. The Crash feed through into austerity and big cuts in starting pay in the public sector, raising public sector churn rates and contributing to problems they have been experiencing. One conclusion is that Government should publish staffing levels in all prisons, public or private, and also vacancy and churn rates (3) Particularly, at Ashfield in the early 2000s, described in my book, in the section 'Four prisons in trouble' – the only other time that Government has intervened to take over a failing privately run prison. (4) Management's insistence on keeping prisoners unlocked, even though for many, there was nothing for them to do is odd, because it appears there was nothing in the contract to require this. (5) Curiously, there were significant financial penalties in respect of this prison in 2011-12 (£95k) and 2012-13 (£205k) – the very years when the prison was doing OK! See Commons WA 5.10.16 (6) “Overall, Altcourse was in some key areas bucking the trend when compared to other local prisons. While it still faced significant challenges around safety, the downward trend in violence and anti-social behaviour was highly creditable. This was in no small part due to the energetic and proactive approach taken by the prison. Levels of self-harm, while still high, were also decreasing and there had been a real focus on ensuring men with these vulnerabilities were identified and cared for. This had been supported by a positive staff culture, a good focus on decency, and an excellent regime that was being delivered consistently….. the director and his team were providing strong leadership, enabling a highly positive staff culture and delivering good outcomes in many key areas. Overall, Altcours e showed that a local prison can provide fundamentally decent treatment and conditions for prisoners, despite facing many of the same challenges as the rest of the prison service. There was much here from which others could learn.“ Stick that in your pipe and smoke it, Guardian! (7) 'Crime, justice and protecting the public'. Home Office, 1990

6 Comments

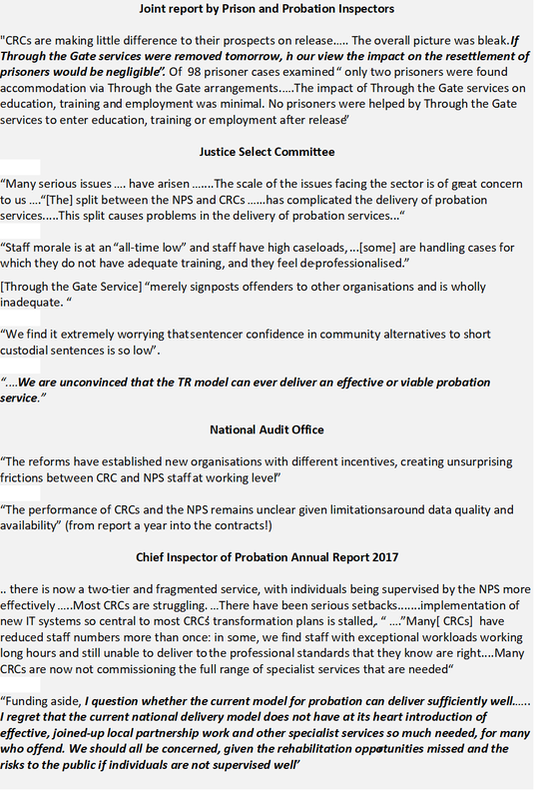

The traditional time for burying bad news is just as Parliament rises for the summer hols. So, no surprise that Gauke chose 27 July to announce early announced termination of the probation contracts (1). For it is a study in failure – one failure heaped upon another. Failure to admit failure A policy that was predicted by absolutely everyone to be bound to fail, has now been demonstrated conclusively to have failed. You might have thought therefore that the statement might include words like 'unsuccessful', if not 'failed', or even, 'sorry'. Gauke is having none of it. This isn't a statement about what went wrong, oh no, it's a 'consultation' on how everything will be done even better in future. (Those SPADs! Worth every penny!) His statement is a masterpiece of evasion. In fact, reading it, you'd be hard put to understand quite why he is terminating the CRC contracts at all. It ought to be a set text for A level politics. First, note the title of the consultation document (2): 'strengthening' probation'. A probation service that, according to inspection reports, and to MoJ's own performance assessments (3), was performing well, has been smashed to the ground and is now lying helpless on the floor. But, hey, let's not dwell on that assault, all we are about is 'strengthening' the victim. Then, the Big Lie: CRCs cut reoffending by 2%, and thus demonstrating the success of privatisation. But he doesn't give the source. or time frame. Nor, of course, does he say what the corresponding figure is for the NPS, similar adjusted for changes in case mix (so embarrassing, if the public sector had done just as well, or better!). I have FoI'd this information and will post it here. Now, I have set out before why I do not believe that changes in the reconviction rate can be attributed to the work of the prison or probation services. In summary:

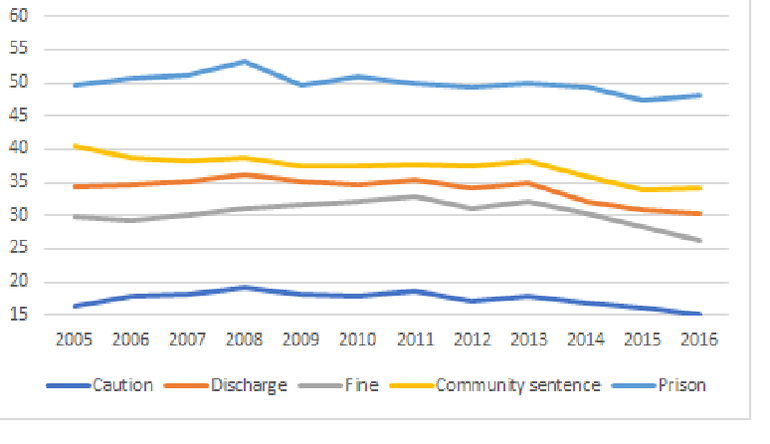

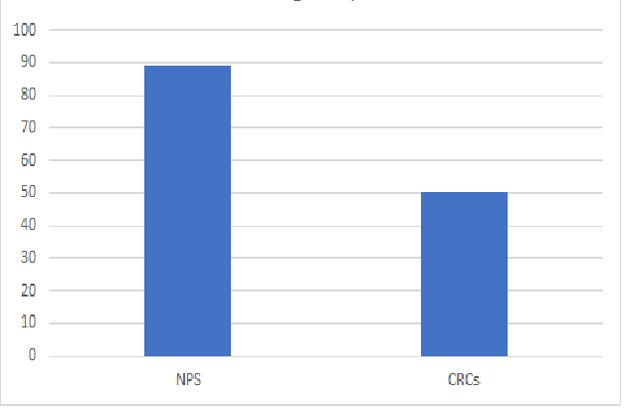

Graph 1: reconviction rates by disposal, 2005-16 .Source: Proven reoffending tables July 2016-September 2016, MoJ. Notes: figures are Apr-June each year. Note: New data source from Oct 2015 It is therefore simply not credible to claim that the fall in reconviction rates for those supervised by the by probation services mark the 'success' of CRCs. It is certainly possible that the work of the CRCs made some contribution, also possible that it did not – but to claim 'CRCs cut reoffending by 2%, therefore privatisation worked' is simplistic nonsense. Gauke continues to elaborate on the 'successes'. ' Privatisation 'opened up the delivery of probation services to a broader range of providers and created the structure that we see today'. Perfectly true. The probation service was hacked to pieces, the pieces flogged off to the highest bidder and that created the chaotic mess we see today. Then, 'there is strength in this mixed market approach, with scope for a range of providers....to continue to bring fresh, innovative ideas to probation services.' That is not the view of the Chief Inspector of Probation: 'We have seen small innovations – a peer mentoring scheme in Kent for example, and three social action projects in Durham – and some aspects of CRC operating models can be described as innovative as well. But there are few signs of innovation in resettlement work, or in other casework. Instead, well-established evidence-based approaches are on the wane, worryingly so '(6). And on through the gate services, 'the few examples of innovation we saw were on a very small scale, so are likely to have no more than a negligible impact on reducing reoffending'(7). But the Chief Inspector does recognise some innovation - though not the kind Gauke lauds: 'Some [CRC staff] do not meet with their probation worker face-to face. Instead, they are supervised by telephone calls every six weeks or so from junior professional staff carrying 200 cases or more. I find it inexplicable that, under the banner of innovation, these developments were allowed' (6). So, how has it all gone? The public sector National Probation Service is performing well, Gauke observes. But CRC contracts have faced 'challenges'. Not 'failure', no – just 'challenges'. What a wonderful word: a 'challenge' obviously isn't the fault of the person being challenged, it somehow just arrives from outside. Moreover a 'challenge' can be quite a good thing, can't it, something you 'rise' to? (Those SPADs again.). But 'difficulties were to be expected'. And that's true - they were 'expected'. So much for the Ministerial view. Privatisation hasn't 'failed', there have just been some 'challenges' and now we can make it work (even) better by cancelling the contracts. Gauke is hugely better than any of his 4 predecessors (but goodness, what a low bar that is!). At least he is willing to state publicly the obvious truth, that our rates of incarceration are far too high and are a waste of money. But he is also a man whose reaction to shocking failure for which he personally is accountable is to dissemble. It needn't be so. A thing I much admired in Martin Narey, when he was head of the prison service, was his willingness to confront failure, own it, and use his own public dismay to fuel determination to improve. Honesty is not only possible: I suggest it also works better. After Gauke, we get into the 'official' part of the document, where there is a little more candour. Yes, the quality of service has been 'falling short' in ' a number of areas'. But the reasons for this are 'numerous and complex'. There isn't a much specificity here about actual performance - so let me supply some. Why not start with MoJ's own metrics: Graph 2: performance against 18 metrics Source: Community Performance Quarterly Management Information release April 2016-March 2017 Ministry of Justice Public sector doing what it says on the tin: private sector not doing what it says on the tin. Clear? Or just review the wealth of testimony from auditors, inspectors, Select Committees. This isn't a few 'challenges' here and there - it's evidence of serious, system-wide failure.

Failure to understand failure Gauke says he wants to 'use the lessons we have learnt so far'. That of course requires one to understand the reasons for failure – as well as being willing to acknowledge failure in the first place. What were reasons? MoJ's view, in the consultation document, appears at first to be that it was just a technical problem - the volumes projections and financial terms and assumptions of the contract (i.e. the guts of any contract!) were all wrong. Specifically:

First: most of these things were known, or should have been known, before the contracts started. The fall in community sentences started nearly a decade before these contracts began. The rise in frequency of reoffending by those getting community sentences has been going on since 2009. And it should have been obvious to MoJ that CRCs should not be judged against a 2011 baseline – 4 years before they started work. CRCs' cost structure should, of course, have been properly researched and understood as part of the procurement process. And that PBR might not be easy to apply the mechanistic way envisaged, and might not produce better results, was very apparent from the ambiguous results from MoJ's pilots in two prisons, but MoJ aborted those pilots early (8). The second thing is that although MoJ ought to have known these things, there isn't the slightest acknowledgement of its culpability in this report. (No surprise, in a Department which in the teeth of all the evidence to the contrary, tells MPs what a strong financial grip it has (9)). Thirdly, this isn't the first time such mistakes by MoJ have caused a contract to collapse: the collapse of the Carillion contract was also due to MoJ contracting on the basis of wrong understanding of cost structures, in that case, their own costs that they didn't understand (10). In short, the document presents the reasons for financial failure as if they were the work of chance or external forces: it fails to acknowledge the extent to which MoJ itself created these difficulties. But, as we read on, its transpires that there were many other serious mistakes and omissions in the contracts, which contributed to the failure of the contracts. It is astounding, for example, that MoJ wrote contracts for resettlement services that specified only one output – a plan, piece of paper – and nothing about what the plan must contain, let along actual results for real prisoners in the real world (7). Hidden away later in that report are appalling figures about the lack of care for the very prisoners who CRCs were set up to see 'through the gate'. 1 in 3 leaves prison with no where to stay, 2 in 3 of those need help with drug abuse on release, don't get it, only 1 in 6 is in a job a year after release. Never mind – there was a piece of paper filed somewhere with their name on it. How could officials think that was adequate? Likewise, as the Chief Inspector also observed (why did it take the Inspector to notice how bad things were – did MoJ not know - or was it hoping no-one would notice?), MoJ was so hands off that it didn't think it necessary to lay down any basic requirement for the nature of probation officer/offender supervision – like, they should ever actually meet (6). Or that they should meet somewhere which gives them dignity and privacy – not a public library for example (11). Likewise, that the contracts don't say much about the content of Rehabilitation Activity Requirement orders (RARs), introduced in 2015, which allow CRCs freedom to do much as they liked. It is conceded that as a result quality is 'patchy' and sentencers 'often' lack confidence in them (contributing to the collapse in community orders and the remorseless increase in custody). Much of what MoJ says it will now do, in new contracts, prompts amazement that they should only think of doing it now, three years into the contracts. MoJ plans to introduce minimum standards and measures of output – you mean, in 2015 you thought it OK to write contracts without them? Some of these appalling omissions of what seem essential contents for any service contract must be put down to Tory dogma, a magical belief, that is refuted everywhere by real world evidence, that freed of all requirements to actually do anything properly or decently, the private sector will just 'innovate' its way to outstanding social results. But officials, too, are surely to blame. I very much doubt Grayling told them not to require anything in the 'Through the gate' contracts, other than a piece of paper, for example. And it is an extraordinary lapse, because the MoJ has not one but two full scale, worked examples of how to specify and monitor complex services for offenders, worked out over many years: the creation of standards for a mixed public/private prison service since the mid 1990s, and the creation of a national probation service in the early 2000s. All these issues about the balance between central specification and local initiative were explored then, and balances set and revised in the light of experience over many years. There is therefore no excuse for having for that balance so extravagantly wrong now. But it's not just another example of poor contracting by MoJ (12). As the many external reports observe, there was a fundamental design mistake in the whole enterprise – the balkanisation of probation into many separate organisations, creating two parallel services in every area, the public sector NPS and private sector CRC. The problems this would create in a service which already had difficultly in working seamlessly with many other agencies, including the prison service, should have been obvious – and were obvious, to the rest of us. It should be obvious to the MoJ also - because much of the consultation report is spent spotting ways in which balkanisation created new problems, and then trying to retro-fit some sort of national coherence to this incoherent model. Examples are the difficulty of ensuring adequate professional raining or standards, or [professional development; difficulties in partnership working with other agencies; difficulties of applying performance measures to results achieved through partnership working; difficulties with data sharing and inter-operable ITC. [MoJs promise to invest in ITC to aid data sharing will raise a hollow laugh in CRCs: this is what the Chief Inspector has to say on the subject: “Despite significant CRC investment, implementation of new IT systems so central to most CRCs’ transformation plans is stalled, awaiting the essential connectivity with other justice systems, yet to be provided by the Ministry of Justice.” (my italics)] Nevertheless, heroically, MoJ manages to ignore the issue of balkanisation completely, or rather, it has to ignore it, because Gauke has already decided that he will not countenance a return to a national service – because that would have to be a publicly run service. This means the report completely fails to identify the basic flaw of the design of this brave new world. Failure to learn from failure MoJ won't acknowledge the extent of its failure, or its own contribution to failure, and mistakenly thinks, or pretends to think, that the reasons for failure are limited to technicalities of the contracts. No surprise, then, that it shows every sign of failing to consider a different approach, one that might stand a better chance of success. Instead, they propose to repeat the failed experiment, on slightly different terms.. It is probable that new contracts which will give the CRCs more money will lead to some improvement in their performance. However the problems due to a fractured, balkanised service will remain. What lessons should have been learned?

To which I add: this saga shows - yet again – that there is a major flaw in our Parliamentary system in that it does not permit Minsters (or civil servants) to be called account for their failures, however catastrophic,if they have managed to move on before disaster is evident. Parliament should change the rules and summon the guilty back to face the music. Starting, of course, with one Chris Grayling. What should be done now? I don't know enough about probation to say confidently what the right model is to adopt now. But I do say that given the lessons spelled out above, it is irrational not to carry out a detailed and objective assessment of an option for returning to a single, national and mainly publicly run probation service. I don't say that as an uncritical admirer of the pre-2015 service. In particular, it was very expensive (figures that follow are from an excellent study by the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies (14) ). In the 7 years from 2000, probation spending increased by an extraordinary 50% in real terms: over 12 year period, numbers supervised rose by much less (40%) than front line staff (65%). It is unclear that the results justified this huge jump in costs. And since then volumes of community sentences have almost halved. Pre 2015 probation also involved wasteful diseconomies of scale between lots of small Trusts, some tiny; and wasteful duplication e.g. of offender programmes for the same offenders in the same areas, as between prisons and probation services. Data I saw in the late 2000s for Unpaid Work in London suggested a hugely inefficient operation. So I think it should be possible to develop a much cheaper public service model than the pre 2015 service, It would be fully integrated with the prison service into a single correctional service, sharing the same back office, procurement etc. functions. In due course the private sector might have another chance in a more sensible way, contracting out both prisons and probation in a significant area e.g. Kent so as to unite prison and community services under one provider, but with properly written and researched contracts and effective contract management (with real teeth and effective step in powers, as with prisons). There are other factors favouring an integrated national service. As this saga shows, the correctional services form an integrated system and it is often necessary to move resources around as workflows change. As shown here, a fractured, partly contracted service makes this difficult. This will again be a problem when Gauke achieves his aim to abolish short prison terms, which will require a shift of resources from the prison system to the community. These changes can't be accurately forecast and it will be tedious if contracts have to be constantly reset as such changes become evident. Similarly with changes in the balance between high and low risk offenders. Gauke wont even mention this possibility, much less look seriously at it. The terms of the 'consultation' preclude it. I wonder why not? He does not strike me as one of the Tory fanatics on privatisation: he has already cheerfully renationalised the Carillion FM service and is proposing a dual public/private track for new prisons. And he's been brave enough in questioning the Tory addiction to incarceration. Renationalisation would increase pressure on Grayling, as author of this disaster: but he has lost much support in the party through the railway cock-ups this year. The only explanation Gauke hints at for not even thinking of renationalising is that he is intent on 'minimising the disruption that more significant reform could entail' - which will raise a hollow laugh from the thousands of staff whose careers were ended or blighted by this wholly unnecsary and destructive privatisation. So its OK to rip everything up when privatising, but not when nationalising? Is it cost? True, an all public, union-dominated model would tend to drive up pay and pension costs way into the future. But MoJ has shown pretty brutal determination to reduce these costs in the publicly run prison service, too much so in fact. And the cost of profit margins, and of procurement, would be saved. In short, Gauke can't know what the balance of costs would be, without doing the appraisal I suggest. I wonder if it's simply this: the Tories are saddled with being the party of endless privatisation, and can't now get off that particular horse, even if they wanted to. After all, Labour is now the party against privatisation: therefore by the law of 2 party politics, the Tories must favour it. I don't think it's even a matter of ideology: who, looking at many disasters of privatisation now crowding our newspapers, could possibly hold any more to the idiot dogma of 'public bad, private good'? Like armies in WW1, the Tories find themselves in the trenches facing the enemy opposite and have long ceased really to believe in privatisation - but 'we're here because we're here because we're here'. At any rate, Gauke's failure to consider a national. public service is another failure, but probably not the last one, in this saga. A final, personal note. I've been asked why I, an advocate of competition in prisons, favour renationalisation in probation. Simple: I favour intelligent privatisation, that produces public benefit: I am against stupid privatisation, that does not. Prison is intelligent privatisation. Probation is stupid privatisation. Notes

|

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed