|

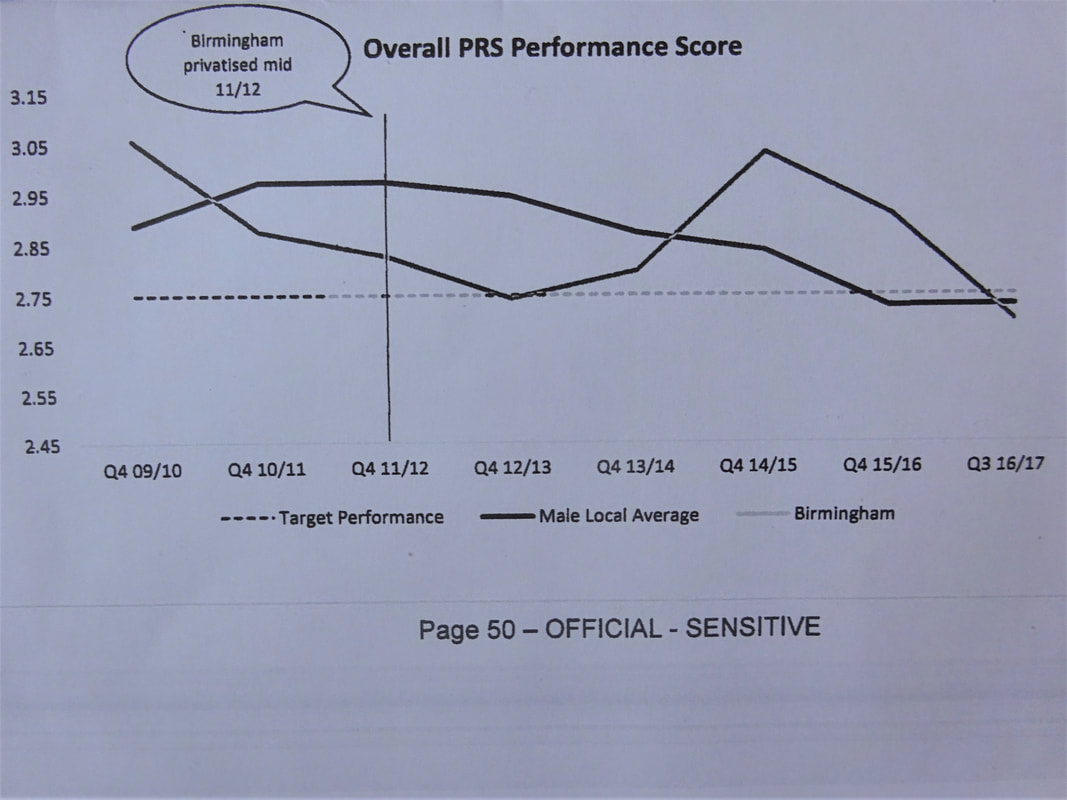

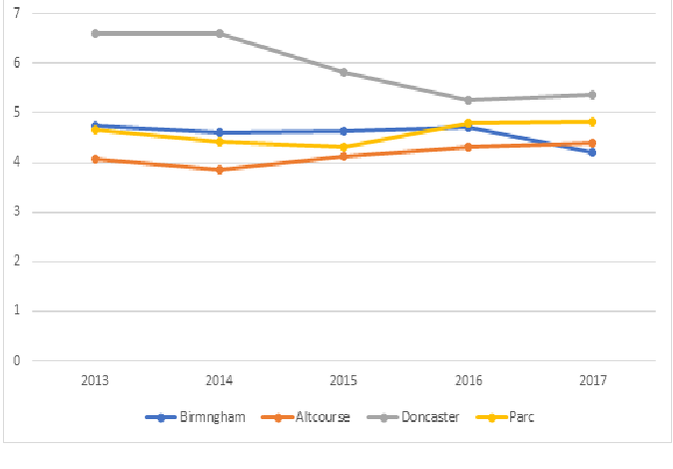

NOTE [added 1 September: I have received quite a few comments privately on this piece; I have summarised some of general interest at the end] I have been reading the report of the internal MoJ inquiry into the major riot at Birmingham prison on 16 December 2016, which had been withheld, but then released this week following a Freedom of Information Act application. It has been redacted, but not much. The report, by a former Director of what was then the National Offender Management Service (NOMS), is a most illuminating document, detailed, balanced, thoughtful. It not only casts light on how Birmingham prison reached the dire state described by the Chief Inspector in his Urgent Notification last week, but vividly illustrates perennial truths about how to run – and how not to run prisons – and what a difficult and important a job that is. Anyone seriously interested in prisons ought to find time to read it. It comprises first an analysis of what happened on the day of the riot, and second how the prison had deteriorated in the preceding 12 months, to the extent that staff had effectively already lost control well before the riot. I am not primarily interested in the actual riot, but the detailed, minute by minute account of the loss of control is as gripping as any film – quite terrifying. It sets the scene by describing how staff shortages and high turnover over many months placed staff, inadequately supported by management, under intolerable pressures and lead to disrupted regimes which in turn fueled prisoner boredom and discontent, and how staff gradually ceded control of the wings to prisoners. Then, on the day, an act of defiance by a couple of difficult prisoners gradually escalated, needlessly, as several opportunities to contain things and regain control were lost due to muddle and lack of grip by middle and senior management. Prisoners reacted to indecision by turning to violence, and soon even those who'd have preferred to stay out of it felt obliged to join in. But the report also records some acts of great courage by staff, in rescuing vulnerable prisoners from danger and holding vital control points despite ferocious assaults by groups of prisoners. One scene sticks in my mind: one wing had been lost, staff were running for safety, but one staff member saw a vulnerable prisoner who he knew would be severely beaten or worse, ran back at great risk to get him and they both then pelted down the wing for safety, closely pursued by a mob. 'The PCO described his good fortune at managing to unlock and secure the gate first time...' I bet he did, but not in those words! Once safe, the prisoner vomited with terror and relief and then would not leave the PCOs side. G4S failed abysmally - but some of their staff past the test alright. I do hope their courage and professionalism has been recognised. The second part of the report analysis how control was eroded over the preceding year or so and it is hugely illuminating. First of all it confirms what I have been saying, that the prison which improved markedly after transferring from public to private sector management in 2011. Two things confirm that. The first is research by Alison Liebling and others which showed improvements on 7 dimensions of prisoners' 'quality of life, as defined and measured by them: ‘respect/courtesy’; ‘humanity’; ‘decency’; ‘care for the vulnerable’; ‘staff-prisoner relationships’; ‘fairness’; and ‘personal autonomy’. Even more marked were improvements in the quality of staff life, including relationships with line and senior management – an extraordinary and important achievement, considering the feelings aroused by of the competition in 2011 and the highly contentious move of existing staff to the private sector, the first time this had ever happened and (as I know) long the source of much worry amongst policy makers (1). This progression is confirmed by NOMS own Prison Rating System, a sophisticated analysis of many aspects of prison operation, over the same period. I reproduce a graph, showing this improvement according to the PRS after privatisation in 2011, up to January 2015, and the precipitous decline thereafter. (Note the steady decline in public sector prisons right across this period). Chart 1: ratings of Birmingham and other local prisons, NOMS Prison Rating System Thus, two lessons immediately: 1) privatisation was not the issue (in fact, privatisation had initially lead to much improvement, albeit from the low level in which previous public operation had left the prison); and 2) the decline began way back - two and half years ago. The report doesn't help pinpoint quite why the prison started its rapid decline around January 2017 though there is some suggestion that the drug problem became much more serious around then, and it was just at that time that assault and self harm rates began to accelerate upwards across the whole system, so the cause or causes weren't peculiar to Birmingham. Staffing levels, and management of staff, are central issues. Mapping the data from this report onto data I previously obtained under FoI, budgeted staffing levels (302 PCOs) have not changed significantly since 2013, and probably not since privatsation in 2011. Neither budgeted staffing levels not the number of posts vacant (about 3%) were out of line with other prisons – on my analysis, the staff:prisoner ratio was considerably better than Doncaster or Thameside, and about the same as Parc. Chart2: Prisoners per PCOs at Birmingham and comparator contracted prisons Source: PQs and FoI applications Note: figures affected by reduced pop after 2016 riot But the staffing situation was nevertheless very difficult indeed – dangerous, in fact - for several interconnected reasons:

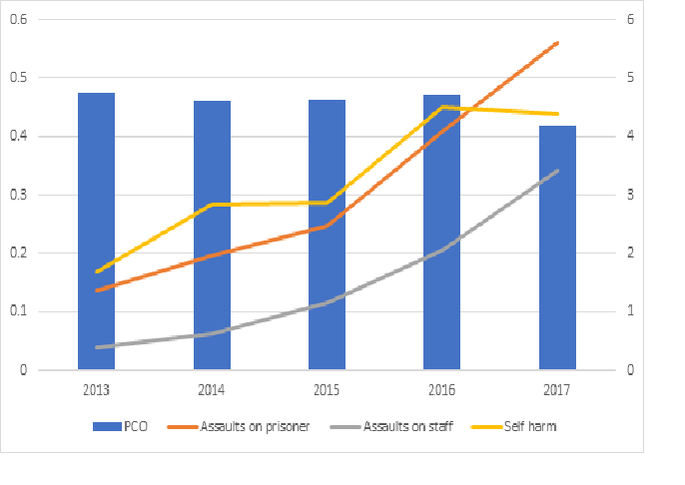

Thus the planned regime simply wasn't deliverable with available staff numbers. There weren't enough staff on landings, prison routines were constantly disrupted and many staff were new, insufficiently trained and scared. As we know from previous breakdowns in privately run jails (3), this quickly become a downward spiral - with new staff appalled at what they are faced with and choosing to quit or, if they stay, adopting passive and defensive behaviours rather than challenging misbehaving prisoners. Staff complained that they were poorly supported: 'new staff....reported feeling ignored and marginalised, and made to feel like a nuisance when they asked for help'. Management was suprisingly weak in many other ways. Managers insisted staff maintain a 'full regime' despite low staff availability - but it wasn't even clear to staff (or the inspectors) exactly what 'the regime' was supposed to be! Policy on unlocking was also unclear and staff seemed to make it up as they went along. The consequence of all this was a gradual retreat from authority, a process so familiar in prisons. Prisoners bullied and conditioned staff into unlocking everyone, whether entitled or not, and the IEP scheme, meant to relate privileges to behaviour, was hugely undermined. Unlocking everyone despite dangerously low staff availability became the norm, with staff unable to reconcile safe staffing minima with management's demand that they to keep prisoners unlocked (4). Staff over relied on prisoner volunteers to keep order, and some of these were not averse to using violence to do that job (and possibly some had other agendas of their own). The jail really had been turned over to prisoners to run! Extraordinarily, prisoners who wanted to be unlocked into this unsafe environment were asked to sign that they accepted the risks, an absolute abdication of responsibility by staff (and G4S). Staff seemed to loose control of such a basic thing as movement around the prison. Discipline was effectively abandoned - in one period only 1 in 6 serious assaults were referred to the police, of 655 cases so referred only 1 in 10 lead to a conviction. Violence went unpunished and drug taking went unchallenged. Vulnerable prisoners were not properly protected. Prisoners' attitudes in such circumstances varies – some relish the lack of control, but others find it threatening and difficult, finding they were unable get the help prisoners need from staff to get things done: “There as too much freedom,we like freedom but there weren't enough staff to deal with it. You weren't made to do anything, no discipline, no structure ...You couldn't find any staff...they let us get away with anything. Every day was a party. But boredom leads to badness”. “Boredom leads to badness” - that should be inscribed above the gate of every jail. The result was soaring rates of drug taking, self harm, and prisoner on prisoner and prisoner on staff violence. Chart 3: number of PCOs, assaults, self harm incidents at Birmingham, all per prisoner Note: PCOs on right hand axis, other data on left axis The management response was hopelessly inadequate. There are processes to ensure data such as assault and disciplinary rates are regularly reviewed in jails and that Governors/Directors regularly assess the stability of the jail. At Birmingham management assessed the jail in the weeks before the riot as 'low' i.e. 'there is no evidence of increased stability or instability above the norm'. That had been the rating throughout 2016, as every indicator turned glaringly red. The report suggests that management had been conditioned to accept very high levels of violence as the 'new normal'. In plain English, management had completely lost it.

And not only management. Each private prison has a number of MoJ officials – 'Controllers' – permanently working inside the jail to monitor operations. Here the report is more reticent, but it appears to confirms what a number of commentators have remarked on, a tendency of the Controllers to retreat into bureaucratic box ticking role. If they had walked the walk and talked to staff and prisoners, and taken a more common-sense over view of the state of the jail they could not have missed the seriousness of its rapid deterioration. But the role of Controller has always seemed unclear, and it's a difficult job to fill, because you need able experienced Governor grades, but such people would rather be off running their own jail. What does the report, on a riot 20 months ago, tell us about the run up to the Chief Inspectors extraordinary intervention last week? Difficult, because until the full report on this most recent inspection is published, we don't know what happened in those 20 months. But I think we can already say:

More general thoughts prompted by reading this extraordinary document:

COMMENTS RECEIVED

(1) In my time it was thought too risky to attempt without much reducing prisoner numbers during transition, something we never had space to do. (2) Rates this high were common in privately run prisons in the early 2000s and as recounted in my book, were key in bringing several to crisis point. Public sector rates were then very low – possibly too low. I had been told that changes in the labour market after the 2008 Crash had brought rates right down, to 10% or so: but clearly, not everywhere. The Crash feed through into austerity and big cuts in starting pay in the public sector, raising public sector churn rates and contributing to problems they have been experiencing. One conclusion is that Government should publish staffing levels in all prisons, public or private, and also vacancy and churn rates (3) Particularly, at Ashfield in the early 2000s, described in my book, in the section 'Four prisons in trouble' – the only other time that Government has intervened to take over a failing privately run prison. (4) Management's insistence on keeping prisoners unlocked, even though for many, there was nothing for them to do is odd, because it appears there was nothing in the contract to require this. (5) Curiously, there were significant financial penalties in respect of this prison in 2011-12 (£95k) and 2012-13 (£205k) – the very years when the prison was doing OK! See Commons WA 5.10.16 (6) “Overall, Altcourse was in some key areas bucking the trend when compared to other local prisons. While it still faced significant challenges around safety, the downward trend in violence and anti-social behaviour was highly creditable. This was in no small part due to the energetic and proactive approach taken by the prison. Levels of self-harm, while still high, were also decreasing and there had been a real focus on ensuring men with these vulnerabilities were identified and cared for. This had been supported by a positive staff culture, a good focus on decency, and an excellent regime that was being delivered consistently….. the director and his team were providing strong leadership, enabling a highly positive staff culture and delivering good outcomes in many key areas. Overall, Altcours e showed that a local prison can provide fundamentally decent treatment and conditions for prisoners, despite facing many of the same challenges as the rest of the prison service. There was much here from which others could learn.“ Stick that in your pipe and smoke it, Guardian! (7) 'Crime, justice and protecting the public'. Home Office, 1990

6 Comments

Peter Bell

27/8/2018 08:17:40 pm

What an excellent article. Will have a look at your book now

Reply

Julian

28/8/2018 01:20:58 am

Thanks. Sorry the book's a bit pricey (I get hardly any of that!). Your work sounds interesting and must give you quite an insight into prisons, and prisoners.

Reply

Peter Bell

1/9/2018 03:10:50 pm

Might have to wait until I get a bit of money! Currently looking for paid work (but lots of voluntary work) and/or starting a CIC

Paula Gilbert

1/9/2018 12:33:30 pm

A really insightful and balanced article, however mirrors a position currently in many establishments whether private or public

Reply

Christian

29/6/2020 03:33:21 am

Fantastic read! Though would you happen to have a link to the actual FOI Birmingham report? Its appears to have mysteriously disappeared from everywhere obvious.

Reply

Julian

29/6/2020 08:57:57 am

How very odd! I will see what I can do. Please email me at levay.julian@gmail.com

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed