|

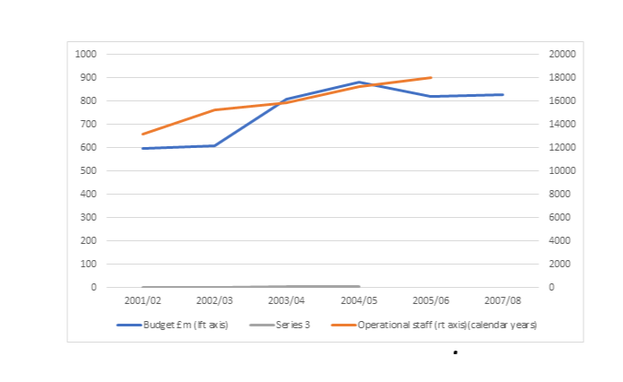

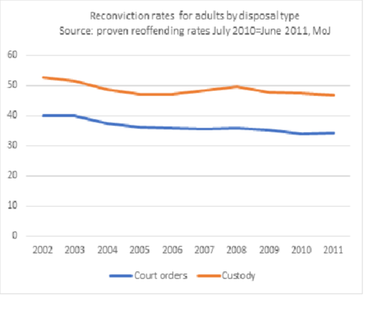

The National Offender Management Service, born 1 June 2004, died 8 February 2017. No flowers by request. The abolition of NOMS last week greeted with a universal lack of interest. It will be little mourned, even though prisons and probation both did much better during NOMS' first decade than either before or since. A difficult birth NOMS was set up following a report by Pat Carter (1). Its conception was unnatural – a forced union of at least 3 different agendas: the introduction of 'end-to-end offender management', reducing the prison population and increasing competition. Its birth was troubled, with Blunkett announcing acceptance of its findings without adequate examination, or real understanding what they implied. And it turned out to be malformed. Carter didn't go into detail and didn't test out his ideas. For example, he failed to notice that Government had no power either to run probation services directly or contract for them (which remained the case til Government legislated in 2007); or that about half of the resources for offender programmes were actually held outside the prison and probation services, so that making them 'commissioners' for such services missed half of the picture. His report also imagined a situation where the Department both ran prisons directly through line management and simultaneously 'commissioned' services from them, a legal and constitutional impossibility which, bizarrely, the current Lord Chancellor is about to re-attempt. An unwelcome arrival From the outset, NOMS was viscerally disliked by many in the prison and probation services, who knew full well how important is was to bridge the gap between custody and community services, but whose tribalism was too entrenched to be comfortable with a merged identity. Probation staff in particular understandably feared being dominated by the much bigger prison service, whose ethos it detested and whose demands for money and ministerial attention always trumped those of probation. All ministers believed in prison: some were dubious about probation. NOMS was seen as a vehicle for ever increasing central control, exercised by a bloated and remote HQ. Figures banded about for the size and cost of NOMS HQ did not distinguish between classic civil service 'policy' jobs, and work that was fully operational and without which prison service couldn't have operated. It was an own goal that NOMS never produced any clearer account. (Of course, there is nothing inherently wrong with centralisation. The chaotic, anarchic nature of the prison service up to the mid 1990s, where key operating instructions were causally ignored locally, sometimes because impossible to comply with, and terrible things shappened as a result, cried out for greater central grip. These things tend to go in cycles in large, distributed organisations. ) Endless surgery If NOMS meant one big change, that would have been one thing – but the organisation was hacked about again and again. Carter's notion of running prisons through both direct management and 'commissioning' – memorably described by Phil Wheatley as 'a plane that could never fly' – wasted years of constant reorganisation, trying to make this misconceived idea work, with the prison service separated out from NOMS as 'just another provider', before it was dropped in favour of plain ordinary line management. This constant shifting around – some units moved several times between the prison service, now deemed to be merely another provider, and the centre of NOMS – alienated many career civil servants in HQ. Probation suffered from an especially bad case of what might be called 'Compulsive Re-organisation Syndrome' or CRS. First turned into the National Probation Service in the early 1990s, then into statutory Probation Trusts in the late 2000s, shortly before being broken up and part-privatised, part-centralised in the mid 2010s. Good people were exhausted, alienated or jettisoned along the way. What they must feel like now - as Government tells the prison service that empowering front line staff and freeing them from central control is - of course! - the way to improve services, and as the CRC contracts look more and more troubled. There is so much talk of accountability, yet no Minister is ever held to account for their botched or unnecessary re-organisations. Missed opportunities It can be said against NOMS that despite these massive re-organisations, it missed opportunities for getting real benefit from them. Prison and probation, far from being brought together, were cemented further into their silos. For example, there wasn't even an experiment in letting prison and probation services in an area as a single contract . Each prison and probation board or trust in an area continued to run their own offender programmes for the same bunch of offenders, instead of running a single programme across institutional borders. And yet....it worked And yet, for all that, the decade of NOMS invention was, looking back, a good one for both services – better than what went before , and certainly much better than what has come after. ...for prisons The prisons system had been in a scandalous state for decades, right up to the turn of the century. But in the 2000s, with the introduction of effective management, a new generation of management minded governors, and substantial money for new offender programmes, there was steady improvement towards much more consistent performance (2). By 2010, the prison service was in a better state, despite continuing high over-crowding, than it had been in living memory. Under the Prison Rating System, in 2010-11 no prison rated in the lowest category (cause for serious concern) and few in the next one up (cause of concern). Compare that with the turn of the century: a serious riot at Lincoln (2002), institutionalised beating in the Scrubs Seg, institutionalised racism at Brixton and many other prisons, the gruesome murder of Zahid Mubarek at Feltham, the near total collapse of Ashfield and Rye Hill! Or compare with 2015-16, when the PRS rated no fewer than 6 prisons as causing serious concern an a full quarter of the system rated as causing concern, and major riots at three prisons. ..for probation Comparisons with probation's pre-NOMS performance is more difficult. Ironically, although prisons are often described as a 'hidden world', the media, and public, know what a 'bad ' prison looks like and excesses in prisons are (nowadays) pretty quickly made public. But 'failure', in probation, is not so easily recognised. What one can is that far from being robbed of resources to pay the prison service, probation did very well in the 2000s. Graph 1: probation resources 2001-08 (from Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 2008 (3)) In fact, a study of resourcing of various criminal justice agencies in this period concludes that "probation appears to have been the main winner" (Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 2008), ahead of police, prisons and courts. In the same decade there were many important advances in the way probation worked: the offender management model itself, which had faults to be sure, but some virtues, better methodologies for offender risk assessment, so crucial to probation (Oasys, VISOR), better inter agency working (MAPPA). And in terms of achievement one can point to the NOMS ratings report for 2010-2011, which found every single probation trust to be giving 'good' or 'exceptional' performance. One can also point to the extremely low rate of serious re-offending by the 50, 000 or so high risk offenders supervised under MAPPA every year; in 2010-11, 'only' 134 were charged with such an offence, and not all convicted, though of course it wil be said that that is 134 too many (4). ...success in cutting re-offending Many now say that the best, or indeed only, measure of the success of prisons and probation is the reconviction rate. I've expressed doubt about that in my last article here. But if that's what you think, have a look here, and then tell me why you still think NOMS in the 2000s was a disaster: Graph 2: success in cutting re-offending 2001-2011 (Source: NOMS proven reoffending tables, 2010-11) Granted it looks like a small reduction, but in fact it is as much as, if not more than, the criminological evidence suggests should be achievable, across the whole offender population. It amounts to many tens of thousands of crimes avoided. What's not to like?

(Indeed, it is very interesting to me that however often attention is drawn to this clear evidence of reduced reoffending, all you hear from politicians, pressure groups and criminologists is that reoffending rates have not come down. I am beginning to suspect that if there is one thing we really cannot handle, cannot accept, it is good news that conflicts with our deep belief that x or y is dreadful. We would much rather, it appears, that x or y continued to be dreadful, or at least seem so, than that we had to admit our prejudices are incorrect. One sees this in florid form in respect of many achievements of the Labour Government, where Labour supporters are far more insistent that nothing good was accomplished than the Tories are. It's a form of reputational self-harm. Because they weren't the right - or Left - sort of Labour Government, you see, so they just can't have achieved anything.) The 2010s I have talked of NOMS' success only in the 2000s. Of course, it was all downhill from around 2013. But one can hardly blame NOMS for that. Whatever the organisational structure, the cuts would have just as been severe, even more so because made without any attempt to manage them, and the mania for privatisation would still have struck. Indeed, NOMS became in a sense the victim of its own success: in a previous generation, the speed with which Grayling made succession of massive changes in prisons and probation would have been simply impossible. NOMS' greater managerial grip lent itself to Grayling's lust for successive massive, unargued, unevidenced, hasty re-organisations. Verdict NOMS was the ugly, unwanted child who was a quiet success. But none of us can bear to admit it. Next up So much for history. The question now of course is why Liz Truss has abolished it, why she has chosen to make the changes she has and what the chances are of them succeeding. I shall return to that question. Notes (1) 'Managing offenders, reducing crime ' (2003) (2) It is de rigueur for criminologists decry 'the new public management' of the late 1990s: what species of management do they think existed in the early 1990s, when the prison service was a basket case? What kind of managerialism would be more acceptable to them? (3) Garside, R. and Groombridge, N., 'Criminal justice resources, staffing and workloads' (2008) (4) MAPPA annual report 2010-11, statistical tables

0 Comments

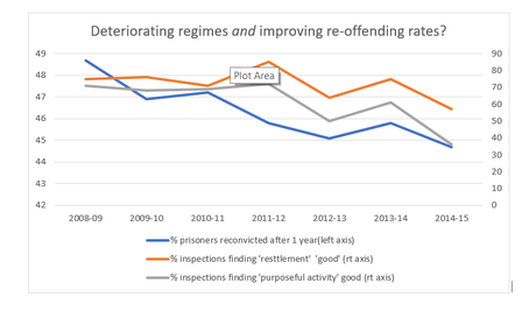

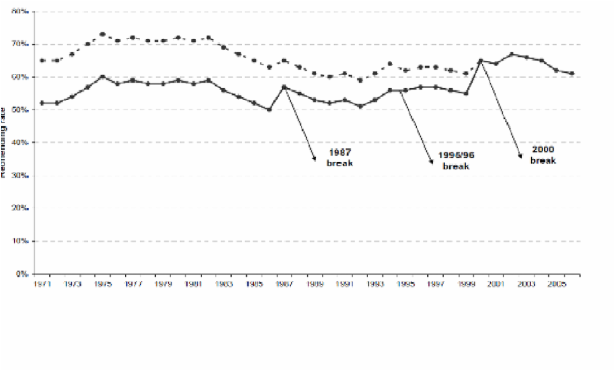

There is a growing consensus that the central aim of prisons is rehabilitation, that therefore their performance is best measured by whether they reduce re-offending and that therefore the ideal measure would be re-conviction rates, if only we could work out how to overcome the various methodological problems (to do with isolating the effect of one particular prison on an offender who may pass though several, and then be supervised after released by probation services). The latest reconviction data, for those released from prison in 2014-15, casts doubt on this last assumption (I will return to the first on another occasion). It shows reconviction rates for prisoners falling steadily since the high point in 2007-08, including a 1% fall in 2014-15 - just as the prison system was reaching crisis point. In the same year, for the first time ever, the Chief Inspector rated 'resettlement' activity as 'poor' or 'not sufficiently good' in more than 60% of prisons inspected, and 'purpseful activity' even lower, at just 36% (it must be said that as the mix of prisons inspected is different in each year, comparisons over time are not precise: nevertheless, the trends here are clear.) Figure 1 : regimes and re-offending trends The disjunction between the trends is starting (graph 1, above). They suggest that the prison service was, at long last, succeeding in cutting re-offending, just as it reached breaking point. Clearly, that's nonsense. A look at longer term trends is also salutary: figure 2 shows changes in re-conviction rates from 1971 to 2006. Again, the sharp downward trend between 1980 and 1990 (on the 'adjusted' line) is utterly counter-intuitive, as this too was a period of deepening crisis in prisons, of the 'nothing works' doctrine in criminology, appalling living conditions, non existent regimes and in 1990, the worst prisons riots in history. (It was after all at just this point that a Government White Paper stated that prisons were “an expensive way of making bad people worse”!). It seems safe to say that if reconviction rates really did fall so markedly in that period, it was not thanks to the prison service.

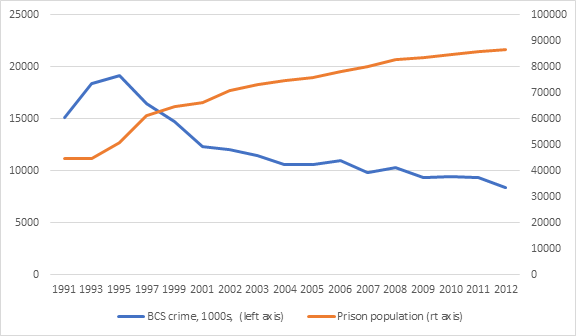

I am not of course saying reconviction rates are useless, obviously we do need them as information: but I am becoming more dubious that they are useful as measures of performance, particularly at the level of a percentage point movement here or there, year on year. (Which is how they are used in 'performance by results' or PBR contracts, which, therefore, are a mistake.) There is a wider point about Government here. The fashion for setting numerical targets for changing social behaviour on a huge scale really got going in the early '90s – curiously, under a Tory Government. I recall Chris Lewis, head statistician in the Home Office, explain to Home Office Ministers then that it was unrealistic for Government to pretend it could control the crime rate: he sounded awfully no-can-do, but of course, he was right. I recall similar protests from the public health people, when I was in the NHS, when numerical targets were set for reducing the suicide rate. Of course, this sort of thing became all the rage under Blair. And continued under Cameron – with the supreme fatuity of a 'national happiness index', which he hoped would 'inform' policy decisions (ONS are still publishing this, though sadly, not their assessment of how far various Government policies have made us happier, or not). It's one thing to say that public services should do their best to help individuals who are suicidal, or who may want to avoid drifting back into crime - clearly, they must, to the very best of their ability. But it's quite another to view the State has having the power to modify human behaviour on a gigantic scale, like a finely tuned machine, It doesn't. And, back in the days when Tories actually were Tories, they would have said: 'and thank God for that'. Before I gave evidence to the Justice Committee the other day, I did a bit of swotting up on what the MPs have said previously on prisons. I noted that Philip Davies MP argues that prison sentences are not long enough (1). Foreseeing a possibly line that doubling the prison population since the mid-90s was the cause of the dramatic halving in crime over the same period, and therefore worth every penny, I sought for a proper study of the connection between the two. To my surprise, I could find none (2) and **. (Come on, criminologists!) Here, therefore, is my home-made analaysis. Let me know if you can do better! Trends in crime and the prison population, E and W, since 1991 Despite the pleasing symmetry of this graph, it seems extremely improbable that the doubling of prison numbers has made more than a marginal contribution to the halving of crime, for the following reasons:

1, Big reductions in crime rates have occurred across the world, including countries where the prison population did not increase (3). Clearly, it is a global phenomenon, not the consequence of criminal justice policies in particular countries, so much so that universal explanations, such as the ending of lead in petrol, have been proposed. 2, Taking the argument of incapacitation (if they're locked up, they can't be committing crimes, at last not against the public), to get from a 40,000 increase in prison numbers to a reduction of 12, 000, 000 crimes a year since 1995 (4), you have to make assumptions about the rate of potential ooffending by those locked up, about their contribution to the overall rate of offending by all offenders, and the likelihood of others 'filling the gap' while they are inside which look completely implausible. [Seealso Addenda]. 3. Taking the argument of deterrence (offenders are so frightened of jail that they give up crime), we know that offenders are very poor at estimating and acting on assessment of long term risk and we also know that what they do pay some attention to is the risk of being caught. But the risk of being caught has barely changed until the mid 2000s, by which time most of the increase in prison numbers had already happened (5) (and there is so much doubt about police crime statistics that they are no longer pubished by ONS (6)). The idea that an offender will reflect and think: well, my chances of being caught haven't changed - but if I am caught, I'm likely to do an extra x months inside, so I won't take the risk, is implausible. 4. International studies that map changes in crime levels again change in prison numbers, especially in the many jurisdictions of the States, have failed to find any conclusive link, but generally indicate that the effect of increased incarceration on crime is likely to be marginal (7). [But see Comment posted below] 5. Activities such as binge drinking by young people. which are not in themselves criminal, so not affected by changes in sentencing, but which are linked to risk of offending, have also reduced over the same period, suggesting again that this is part of a general change in social behaviour (8) 6. The reverse case: the rise in crime since WW2 up to the mid-90s was not accompanied by a falling prison population. Both the remorseless rise in crime up to 1995, and the remorseless fall since, seem very unlikely to have much to do with the activities or policies of the criminal justice system. Society changes: we speculated what drove crime up: we now speculate what drove it down: but we don't really know. Or, as a Tory of another age put it: “How small, of all that human hearts endure, That part which laws or kings can cause or cure.” Which leaves open the question of why we have twice as many people in jail as 25 years ago, at vast and, it now turns out, insupportable cost. ADDENDA ** I have since come across a study which sought to model the impact on crime rates of increasing the prison population in the UK, R. Tarling 'Analysing offending: data, models and interpretation' (1993). Tarling's elaborate modelling estimated that based on incapacitation alone, a 25% increase in the prison population would achieve a 1% fall in crime, though noting that better results would be achieved in the criminal justice system managed to target high frequency offender (which it never has). Tarling's figures were an underestimate because he did not consider the impact through deterrence. The conclusion is that the estimated impact of increased imprisonment on crime rates must vary considerably depending on the assumptions used, but is likely to be pretty small. Notes (1) There is of course a reasonable case for increasing prison numbers - if we somehow succeeded in apprehending and convicting a larger proportion of serious offenders. But that seems vanishingly unlikely to happen, and certainly isn't the cause of prison numbers rising so much to date. (2) The Carter report, 'Managing offenders, reducing crime' (2003) suggested that about one sixth of the fall in crime could be attributed to increased use of imprisonment - but gave no source or evidence for this assertion, and the Home Office have been unable to shed any light on it. [see Addenda] (3) 'Exploring the international decline in crime rates', A. Tseloni et al., European Jo. of Criminology, vol 7, issue 5, 2010 (4) 'Crime in England and Wales: year ending June 2016' ONS, 2016. (5) 'Crimes detected in England and Wales 2011-12', P. Taylor and S. Bond, Home Office Statistical Bulletin 08/12, 2012. (6) http://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/commons-select/public-administration-select-committee/news/crime-stats-substantive/ (7) 'The growth of incarceration in the Unites States: exploring causes and consequences', J. Travis et al., Nation Academies Press, 2016. (8) 'Adult drinking habits in Great Britain: 2013' ONS 2015 |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed