|

The White Paper, 'Prison safety and reform', published in November, contains some good and important things, but overall, it is a political document, intended to evade, not address, the central issues. Here are the two papers I put to the Justice Committee, one an overview, the other on organisational changes. JUSTICE COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO PRISON REFORM, SESSION 2016-17 FURTHER EVIDENCE SUBMITTED BY JULIAN LE VAY: COMMENT ON THE WHITE PAPER Summary The White Paper:

Analysis 1. The White Paper ('WP', numbers refer to paragraphs) contains promising proposals, particularly:

2. But the WP is fundamentally unsatisfactory, on seven counts.

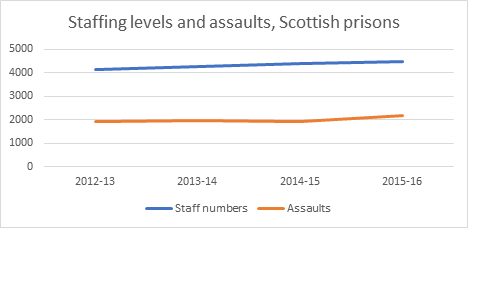

Conclusion There are good and important things in the WP. But overall, it presents a wrong diagnosis, and a false prospectus for recovery. Annex A: comparison with the Scottish prison service Notes: SPS and NOMS stats. Staffing data for publicly run prisons only. Difference is not due to absence of NPSs in Scotland: see “Understanding the patterns of use, motives, and harms of New Psychoactive Substances in Scotland” Scottish Government, November 2016.

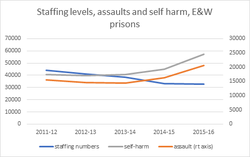

Annex B: misleading use of statistics The WP is keen (172) to blame rising violence and self-harm since 2012 on changes in the makeup of the prison population. This passage is misleading in its use of evidence, in several respects:

Annex C: Uncertainty about building plans The WP proposes:

There is a lack of clarity on key points:

2 Comments

EVIDENCE SUBMITTED BY JULIAN LE VAY

Summary (numbers are WP paragraphs)

Splitting 'policy' and 'operations' within MoJ 1. The WP says there is a need to clarify roles and accountabilities. In fact, its proposals for the role of the MoJ, and the relationship with Governors, are themselves riddled with ambiguities, and threaten to create a system that will quickly be revealed as unworkable. 2. The WP apparently proposes to split policy making and resource planning and allocation from line management of the Service (68-70 including notes to fig.1). Ministers would, apparently, decide on policy, standards, priorities, targets, resource levels and resource allocation and response to Inspection recommendations entirely separately from NOMS, which would be reduced to line managing prisons whose budgets, targets and performance agreements have all been decided elsewhere (a strange sort of line management!). This will, apparently, require a new entity in the centre of MoJ separate from NOMS, presumably staffed by civil servants who have never worked in prisons and who bear no responsibility for what happens in them. I say 'apparently' because the WP is remarkably coy about this change. There is however independent verification - a report the on the removal of finance, procurement and HR staff from NOMS to MoJ, reported in ‘The Guardian, 12 December. 3. There is a warning from history here. Lord Carter's report 'Managing offenders, reducing crime' (2003) envisaged that the Home Office (as it then was) would both line manage public prisons, but also through a separate structure contract for services from those same prisons. Several years were wasted trying to put that into effect (“a plane that could not fly” - Phil Wheatley). The outcome was to recognize the reality of line management - and it was effective line management that then drove big improvement in prisons in the later 2000s. But this is much worse than Carter's idea – at least with that, line management and commissioning came together under the CEO of NOMS. Here, Minsters will have two sets of advisers on prisons: the person who runs them, and someone who does not. 4. This is a recipe for constant confusion and conflict, poor decision making and blurred accountability – at a time when clear direct and accountability are essential. Consider the following scenarios. Who advises the S of S:

5. Or does the S of S call both sets of advisers before her, and herself try to arbitrate between them? 6. I have been involved with the vexed question of how to manage this politically sensitive, distributed, complex, high risk operational service, on and off, since the Callaghan Administration, and have seen many a man-made mess-up. But this is, by some margin, the worst idea I have heard of. The worst of it is, it is completely unnecessary; indeed, it is completely unargued. The general reader might not even spot it. Nor is it politically at all in the interests of the S of S: her interest lie in having a single, trusted, experienced adviser on prisons who knows how prisons work, how they are actually working but who understands and responds to political needs and priorities, and who can reliably get problems fixed quickly. She has one of those right now. The relationship between MoJ and Governors 7. The WP is also hard to understand on the crucial relationship between centre and Governors. But it appears that Ministers will have direct relationship with each Governor, setting their budgets and 'performance levels through a 'commissioning' relationship. While definitions of 'commissioning' vary, it usually means the job of stating the need for a service, that a variety of providers are then asked to deliver - a more distant relationship than line management. The two sides – the Governor, and the S of S or someone within MoJ acting for her (not, apparently, NOMS line managers) - will 'negotiate' a service agreement. 8. This is unreal. A distanced relationship between Government and schools or hospitals is possible, because their staff have never been part of the central Departments. But every prison officer, on every landing of every prison, is a MoJ civil servant, in line management ultimately to the Permanent Secretary. The S of S, whether she likes it or not, is accountable to Parliament for every last thing done in prisons: so are the Accounting Officers. Efforts to distance themselves from operations are bound to fail – as Michael Howard could testify. 9. Governors cannot 'negotiate' a deal with the S of S, as though as equals. Of course, there can and should be full discussion: but ultimately, Governors like other civil servants, are servants of the S of S and are subject to her instructions as to budgets and targets. Nor can such an agreement be in any way binding: the parameters constantly change {and a critical one, prisoner numbers, is outside anyone’s control). Consider how such agreement would have fared in the past: with the population surge from 1992; the huge, sudden cuts under Mr Grayling; his contracting out of services within prisons; policy changes such as earned privileges or anti-racist or gender equality programmes that are not optional or for 'negotiation'. Or indeed, changes now contemplated – such as the dedicated officer scheme. Minsters are constantly intervening to change priorities and requirements, sometimes for good reasons. Nor are Ministers likely to behave differently in future! Intervention 10. Equally unreal, and positivity dangerous, is the implication that the centre will only intervene if 'performance is of serious concern' (70) or if a prison performs poorly (82). The improvement made in the 2000s was through identifying and tackling potential problems through line management before they became serious. Line managers cannot sit on their hands and watch problems grow. And they will not be allowed to, by Parliament, or the media, and therefore by Minsters themselves. Many other questions arise - the S of S may direct the head of NOMS to intervene in case of failure to act on Inspectorate findings – does this mean Inspectorate recommendations are binding? If not, who advises the S of S on whether to accept them? Who judges what form and level of intervention is appropriate? 11. The WP spells out proposals for how intervention will take place (83). Actually, it looks exactly like what happens now, except for two things: lack of clarity as to who calls the shots between MoJ and NOMS; and the complete absence of the idea of market testing of failing prisons, further evidence that Minsters may be preparing to ditch competition. Devolution to Governors 12. In my first submission, I argued for the approach now being taken – pragmatic devolution to Governors within existing structures, rather than an ideologically-driven model of wholly autonomous prisons, which would require legislation and wholesale reorganisation the evidence of practical benefits emerging from the first prisons is already impressive. 13. But this 'variable geometry' model is a sophisticated one, posing considerable challenges and risks. The prison system is designed to operate as a national one, with a great deal of prisoner movement between prisons (unlike, for example, schools). Too much local variation could make this difficult or may even prove legally changeable. Then there are the costs: a lesson from the Academy programme is that costs will rise considerably, but may be difficult to identify. We should recall that the great increase in central direction under Mr Grayling took place for a reason - because it seemed the only way of making enormous cuts extremely quickly, by nailing costs down in fine detail. Yet there are no costings in the WP. There is a clear risk that the £100m meant to fund 2,500 more staff is sucked into creating new local management capacity that will be essential to operate devolved functions effectively. The following questions arise. local costs 14. Operating costs in prisons will rise significantly. Governors will need expertise on HR, contracting and finance, and in specialist areas such as education, and legal advice Some have appointed an additional 'Executive Governor'. They will need information and systems that they do not have (for purchasing for example), legal services etc. Additional costs per prison seem unlikely to be less than £400k or £40m for the whole system. All these local spending will need to be audited. There is no new money for this, therefore an obvious risk that service delivery will be cut to meet these costs. What is MoJ doing to monitor and control this cost rise? Where does it think, the money will come from? How will they know that the extra cost has been worth it? central costs 15. Ministers will be hoping that as functions are devolved, money can be saved on work now handled centrally. But because of dis-economies of scale, extra local costs from devolution must much exceed savings from centralised back office functions, created very recently precisely because cheaper done centrally. The Academy programme significantly over-estimated savings from decentralising functions from local authorities to schools for this reason. Moreover, so long as some prisons choose to use central services, they will still be needed, yet they will become progressively more uneconomic. How will NOMS manage this? contracts for FM and resettlement services 16. It is only recently that Mr Grayling let nationally contracts for FM and resettlement services in prisons in part to save money, so that Governors are not the customer for these contracts. Neither seems to be doing well, judging by Governors complaints and audit reports. The WP already looks ahead to ending them (150)! This is typical of the chaotic approach to prison policy in recent years. procurement 17. Enabling Governors to contract directly for regime services makes good sense, to them to tailor and integrate regimes and make better community links. But prisons consume hundreds of millions of pounds of goods and services which are generic and must be purchasable more cheaply in bulk contracts across 100 prisons, or regionally, rather than prison by prison – food, energy, clothing, building material. So it is surprising to see the WP suggest local food purchasing (157). If discretion to withdraw from central contracts is unfettered, costs will rise by tens of millions (and the extra costs, including processing and logistics, may not all be readily identifiable). Remaining central contracts would become increasingly unviable. How is NOMS going to monitor and manage this? 'what works' 18. One of NOMS achievements is to amass a respected evidence base of what works in reducing re-offending. Will Governors be free to ignore this evidence base? The WP says new approaches will be evaluated - but that is costly and takes years. In the past, we have seen strange ideas in some prisons – Christian-based regimes (shades of Faith Academies), vitamin therapy and so on. Private prisons 19. The WP silence on privately run prisons, which are in as bad state as publicly run ones, is astonishing. They house nearly a fifth of the prison population and represent a 25-year experiment in doing precisely what the WP now advocates - letting go of direct line management and empowering local management. But Ministers seem uninterested in learning any lessons from that. (Since privately prison have not consistently outperformed publicly run ones, the lesson might be that devolution does not make an enormous difference to performance.) 20. One possible explanation for the silence is that, foreseeing an imminent conclusion to the Serious Fraud Office's 3 year investigation into the miss-payment of £300m to SERCO and G4S on tagging contracts, Ministers are keen to maximise distance between themselves and these companies, and perhaps contemplate ending competition altogether. 21. Nevertheless, these contracts remain for the time being (and in the case of some PFI prisons, for many years to come, because ending them now would be extremely costly), so the issue of how the WP applies to privately run prisons needs to be addressed. For example, do they get a share of the £100m for new staff? If not, why not (we know their budgets were cut, too)? Will their contracts, which contain an excessive amount of central prescription, be re-worked so as to give Directors of privately run prisons the same or greater freedoms? Will they also benefit from taking on local contracting for education and co-commissioning for health? Performance information and league tables 22. The WP is very critical of existing performance information ('focus too heavily on processes and box ticking' - chapter 3, summary). In fact, both NOMS and HMIP operate extremely sophisticated performance measurement systems, that both capture the complexity of prison life and its multiple purposes and yet also condense data into an overall rating, so that one can 'read' a prison's performance. These have been successful. NOMS performance information drove, and demonstrated, improvements in the 2000s. HMIP's ratings showed early on how the Service was starting to fail. Condemnation of existing information seems ill-informed. And, when it comes to it, the WP's ideas are very largely a re-hash of existing data (see Annex below); or promises to develop some ideal measure – for example, of the quality of prisoners’ family lives! - at some time in the future. 23. There are problems with the WP proposals. By using a range of data, without condensing them into an aggregate rating, the WP would make it harder to rate overall performance, which is easily done now. Some proposed measures make limited sense for prisons which do not release many prisoners directly. Omission of overcrowding rates, when most observers consider reduced overcrowding a prerequisite for all reform, is odd. It is unclear what purpose league tables will serve. They make sense in services where users have a choice, such as schools or hospitals, and they inform that choice, and thus exert a kind of market pressure, at least in theory. There is no such dynamic here. The only customer is MoJ, which does already has all the information needed to spot prisons in trouble, and has no need for published league tables. Annex: proposed league table performance measures (101) |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

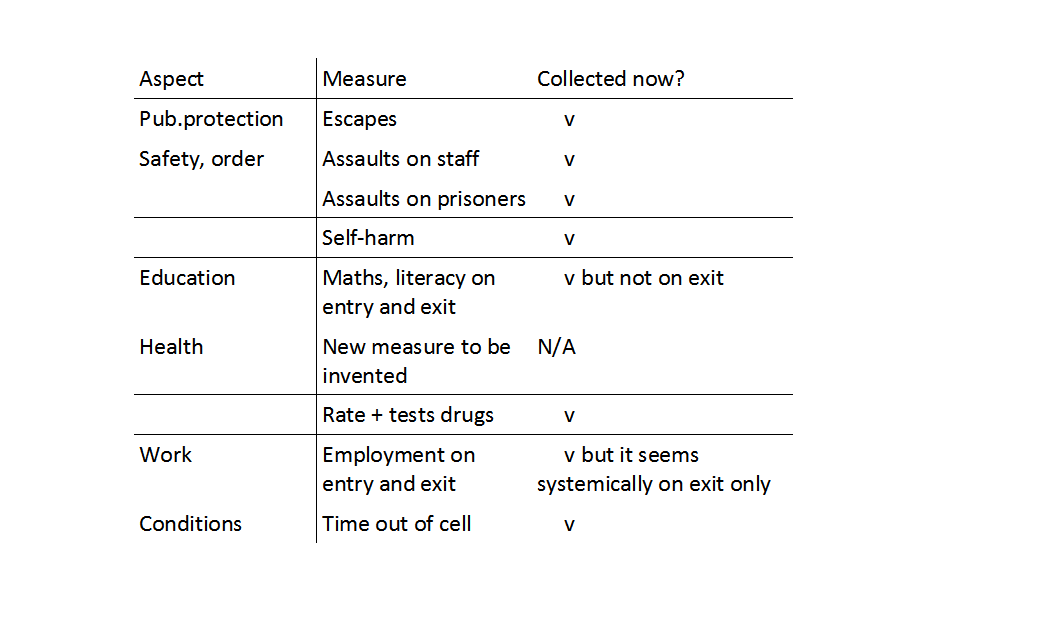

RSS Feed