|

The White Paper, 'Prison safety and reform', published in November, contains some good and important things, but overall, it is a political document, intended to evade, not address, the central issues. Here are the two papers I put to the Justice Committee, one an overview, the other on organisational changes. JUSTICE COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO PRISON REFORM, SESSION 2016-17 FURTHER EVIDENCE SUBMITTED BY JULIAN LE VAY: COMMENT ON THE WHITE PAPER Summary The White Paper:

Analysis 1. The White Paper ('WP', numbers refer to paragraphs) contains promising proposals, particularly:

2. But the WP is fundamentally unsatisfactory, on seven counts.

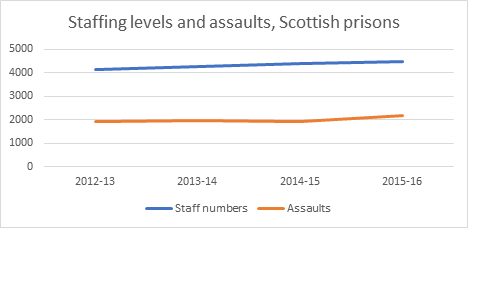

Conclusion There are good and important things in the WP. But overall, it presents a wrong diagnosis, and a false prospectus for recovery. Annex A: comparison with the Scottish prison service Notes: SPS and NOMS stats. Staffing data for publicly run prisons only. Difference is not due to absence of NPSs in Scotland: see “Understanding the patterns of use, motives, and harms of New Psychoactive Substances in Scotland” Scottish Government, November 2016.

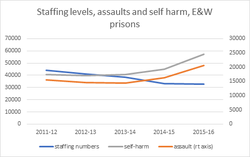

Annex B: misleading use of statistics The WP is keen (172) to blame rising violence and self-harm since 2012 on changes in the makeup of the prison population. This passage is misleading in its use of evidence, in several respects:

Annex C: Uncertainty about building plans The WP proposes:

There is a lack of clarity on key points:

2 Comments

David Barrie

20/1/2017 05:59:23 pm

Well said - especially the remarks about the complete failure to address the central issue of sentencing policies that have led to a doubling of the number of prisoners over the last 20 years.

Reply

william

23/1/2017 04:36:53 pm

Sadly, this is about right. Huge missed opportunity!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed