|

I have been campaigning some 2 months now for the 'Remain' vote in the EU referendum – the first time I have done anything like this 1966 (I could see the students I work with thinking: 'Did he really just say....1966?').

It's an odd experience, because to when I meet Brexiters, and they tell me why they want 'out', I tell them I agree with much of what they say. The EU is undemocratic (you can't vote its government out or, for that matter, in); the Euro has been a man-made disaster, condemning a whole generation in the south of Europe to worklessness and poverty; massive subsidies to one industry, farming, make no sense; we can't control our own borders, and immigration is putting intense pressure on services and housing in the South East; internationally, the EU has been hopeless, first provoking and then appeasing Putin, and endlessly dithering about the migration crisis; in many EU countries, xenophobic and racist parties are coming to power. So why on earth, they ask, are you on the 'Remain' side? Because this isn't a vote on whether the EU is a good thing or not. It's not choice between a good thing and a bad thing. It's a choice between one unappealing but known option, and an unknown one that that promises utter catastrophe. Here's why I am campaigning for 'Remain':

Campaigning is itself re-shaping my views. Oxford is a very international city, and out canvassing I meet many foreigners living and working here, from Europe and beyond. And when I ask what they are doing here, it is all so positive and future-looking – research teams drawn from the best the world has to offer, new tech companies and so on. We should surely be delighted such people want to come here. Others, less qualified, say that they can't prosper in their own countries because of oppression and corruption and bureaucracy, while they know that if you work hard here, you can make something of your life. These aren't people drawn here by our pitiful benefits or free but faltering healthcare (it may be different in other locations, I concede.) Yes, there are too many of them and I don't know what the answer is - but surely not to make the UK a poorer and less appealing place. And when I speak to Brexiters, while some voice concerns I share, others, especially the elderly, strike me as essentially reactionary, resentful of much that has happened in their lifetimes. I'm struck by how unrealistic their expectations of Brexit sometimes are – streets full of British-made cars again, said one. Or, 'we shouldn't have so many Muslims'. Or, 'we can trade with the Commonwealth instead' (a young Australian I stopped said, 'stick with Brussels mate - for my generation, the Commonwealth is just stuff in history books'). Exposed to these influences, I begin to accept what my children have long been telling me – that the age of traditional national identify and national borders is fading, and something more fluid and international is taking shape. And to see that might be a positive, promising thing, that might outweigh the pain of sloughing off some of the past. I have begun to see Brexit as essentially a hopeless attempt to turn back the clock – hopeless, because I don't believe history ever works like that. History is not stasis, it is not the imagined golden age, but change, continuous, challenging, difficult change. Brexit wouldn't land us safely back in 1960, but somewhere quite different. Better to swim with the current and to make for somewhere appealing, than exhaust ourselves trying to swim back upstream. I also begin to think, if we do remain, we shouldn't settle any more for just staying in reluctantly, jeering from the sidelines at the mess the foreigners have made. We should get stuck right in, take up the leadership of Europe, make the damned thing work, or at any rate, make it slightly less of of a demoralised failure. I even found myself thinking: if it were really democratic, would a united Europe be such a very bad thing? – before I come to my senses and recall how deeply happy we are with Westminster, and how wonderfully well it serves us. Looking at the national campaign, no politician emerges from the campaign with any credit. Cameron has played roulette with the country's future in order to stay in power (and seemingly, may now have failed even at that). In his slur against Obama and absurd invocation of Hitler, Johnson has revealed himself to be unfit for high office, lacking judgement and self control: beneath the schoolboy jokes, schoolboy nastiness. Corbyn has let us down unforgivably by his too late, too lukewarm entrance to the fight, praying in aid an abstract, idealistic internationalism that means nothing to 99% of the British people. The referendum offered him a huge open goal – hopelessly split Tories risking deeper and longer recession in pursuit of atavistic and unrealistic nationalism – which he then studiously ignored. Corbyn's weakness isn't his 'extremism' – it's that he simply isn't a politician at all, in the sense of working out what people think and then pushing them and energising them in his direction. He has also, by endorsing Remain while seemingly remaining privately anti-EU, blown his reputation for fearlessly speaking what he thinks. Farron remains the Invisible Man of British politics – what is wrong with that guy? Only Gordon Brown has shown real statesmanship, breadth of vision, and a fluency and conviction that was utterly lacking when he was in power. This referendum raises questions about the use of referenda to settle settle huge, complicated long term issues on which the country is divided. Yes, you can count up the votes and say A got so many more than B, but you haven't solved the division in the nation, in fact have made in much more obvious and bitter. And if the country were to be committed to a radical change of direction on a 1% difference, on a turn out of 60%, with half the electorate not bothered or just confused or bored, and another 6 million adults not registered at all – is that really a triumph for democracy? I am not saying we'd rather not have a vote, but doing this way hasn't felt too good. None of us know what the result will be. The pollsters are still confounded by their collective failure on the 2015 election. And a one off referendum is far harder to predict, because so many are still undecided, and because polling relies so heavily on the precise weighting of a very small sample - for willingness to actually vote on the day and so on. And for a referendum there are no historic data to support weighting. So we're flying blind, really. My own instinct is that it may well be a narrow majority for 'Leave'. I say that partly on these facts – we know that the age group most in favour of 'Leave', the over 55s, are almost all registered and about three quarters of them do actually vote. We know that the age group most in favour of 'Remain', 18-25, only about two thirds are registered and barely half vote. So one old person has three times the say of one young person. The incontinent nostalgia of the old triumphs over the bovine apathy of the young - where was our Bernie Sanders? I also sense, out canvassing, that the 'leave' vote is solidifying, crystallizing out of the 'don't knows' as it were, while the 'Remain' vote stays somewhat soft: The best lack all conviction, while the worst Are full of passionate intensity. I see in the typical Brexiter – who end to be over 40, white, not university educated, not in the liberal professions – a sort of truculent determination. They've been told for so long that they simply mustn't talk about immigration – mustn't even think about it. Now at last someone is saying their worries are legitimate and yes they can do something about it, that if they vote 'Leave' the foreigners will go, and the jobs and houses will be available for them and their children. They close their ears to warnings of economic catastrophe and march determinedly towards the precipice. I dread a 'Leave' vote, as I have never dreaded any election result (which, after all, can always be reversed after the winner has 5 years to show what a disastrous mistake voting them in was). 'Leave' would set us irreversibly on a different historical path, one I believe would doom us to be a substantially poorer, fractured, smaller, more inward and backward-looking country, an object of pity and derision internationally, and with Scotland gone, a rump even less sure of its identity than now, our European neighbours blaming us for the damage we have done, and we in turn blaming them, and each other, for our new status as excluded has-beens - a sad place indeed to live in. A place to emigrate from, not to. Can we really be about to commit such a monstrous act of deliberate self-harm?

7 Comments

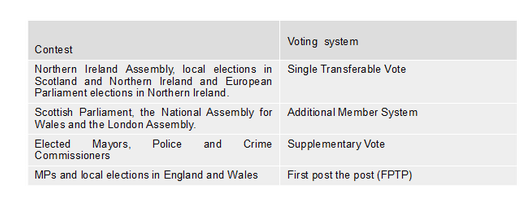

In all the commentary on last week's elections, one aspect that I haven't seen remarked upon is that we now have an bewildering plethora of different electoral systems for different parts of the UK, indeed for different contests in the same part of the UK. Thus: I trust that's clear. Oh, sorry, I forgot that ancient bastion of our liberties: How to account for this? The main factor seems to be the determination of the main parties at Westminster first to 'fix' the Celtic fringes so as to avoid one party domination and encourage the children to play nicely with each other; and second, to ensure that they themselves shouldn't ever be forced to share power at Westminster. Labour and the Conservatives would rather take turn and turn about at unfettered single party government, than find themselves having to share power and make compromises.

In consequence, we always have a national government for whom only a minority have voted. And as turnout may be no more than 60%, and as the Electoral Commission estimate some 6 million people eligible to register don't do so, we are talking about UK governments routinely elected by no more than 20% of the adult population. No British government has been elected by a majority of votes cast since 1931. By contrast, in Scotland the SNP has just achieved 47% of the constituency vote and polled twice as much as its nearest rival in both constituency and regional votes, but is still short of a majority in the Scottish Parliament. But we can't just blame the politicians. The great British public overwhelmingly rejected proportional representation for Parliament in the 2011 referendum (which made such little impact that I just now thought to check that it actually occurred). Even the Scots, who have PR in their own Parliament, rejected it then for Westminster – go figure! Nor does anyone, left or right or centre, now seem to have a good word to say about the 2010-15 coalition government, the first since the War, - not even (perhaps particularly not) the Lib Dems. We seem to prefer our national governments strongly flavoured, undiluted as it were, however much we complain about their unwillingness to compromise when they are in power. And of course, FPTP tends to 'solidify' the two party system – it's very hard for a third party to gain seats. So the system is self-preserving (so much so, that in psephological circles, this is known as Duverger's Law). Of course, there are other electoral anomalies also. A voter in a tiny constituency such as the Western Isles have five times as much say as one in the Isle of Wight, the largest constituency. You are judged old enough at 16 to elect your government if you live in Dumfries but far too immature if you live a few miles away in Carlisle. These anomalies too are explained by purely party calculations. The SNP and Labour want lower voting ages because young people vote for them: so the Tories oppose it. Labour are unkeen on more equitable constituency sizes because they would be the losers. Labour favour block registration of all students, without their involvement, because they tend to vote left: the Tories moved to individual registration or the same reason. The day any party votes for a change in the electoral system that disadvantage it is the day pigs will fly in earnest. (One anomaly that can't be explained by party advantage or indeed, be explained at all, is that both Commonwealth and EU citizens resident here can vote for the Scottish parliament and Welsh Assembly, but only the Commonwealth ones can vote for Westminster. The idea seems to be that a Frenchman is obviously foreign but a Namibian isn't). And so we acquiesce in this strange patchwork of systems which means that, for example, a Welsh or Scottish voter in theory makes one set of calculations within one system to send a representatives to Cardiff or Edinburgh, another to send one to Westminster and yet another to send one to Brussels. One wonders who many voters understand the different systems. Yet their different mechanisms have important consequences for us all. Still, in the old psephological joke has it, the trouble with all conceivable electoral systems is that they invariably result in the election of – politicians. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed