|

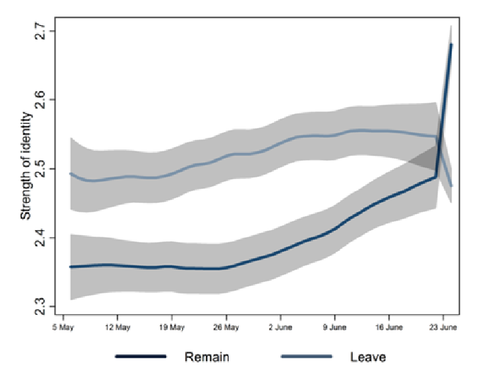

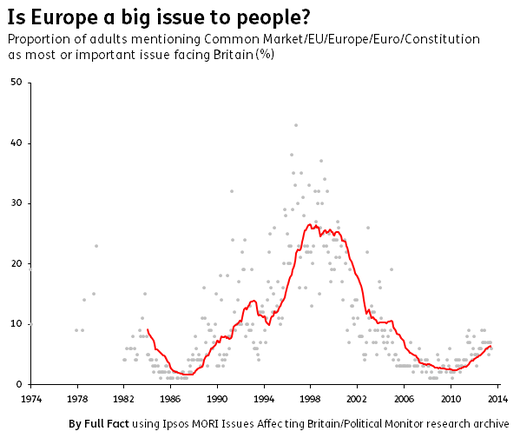

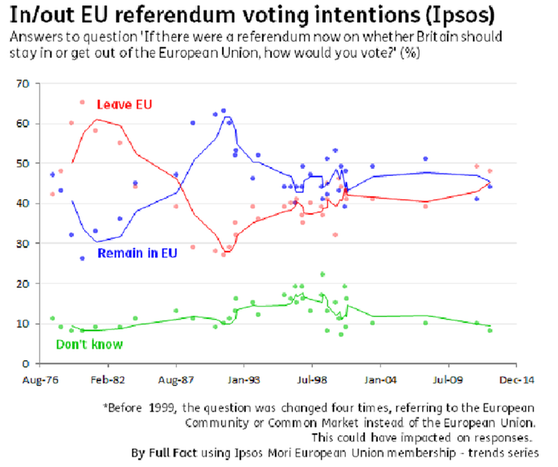

Can it really be only a year since we voted for Brexit? It seems so much longer. One cannot any longer mentally take oneself back to the time before, when we were accustomed to being in the EU and didn't for one moment believe we could really ever be so stupid as to vote to leave. It's the same about the 2008 crash; one can't really believe now that there was a time when the only question was just how fast pubic services and benefits should grow, and which should grow fastest. How on earth did we come to this? I've been thinking about it since offering myself as a subject to an academic who is exploring just that question: how did individuals assume the positions they now have, Remain or Leave? Particularly since in the years just before the Referendum, it's pretty clear that most us, whether pro or anti EU, simply didn't care that much. In 2014, when what were the most important issues facing the country, just 4 % spontaneously mentioned the EU. It wasn't even in the top ten concerns that people had (1). Of course, the UK's relationship with the EU (previously EEC) has always been fraught. Public opinion had been volatile, not to say skittish, over the decades. We joined in 1973 without a popular vote. Twice before Cameron, Prime Minsters riding a wave of popular antipathy towards the EU negotiated improved terms before securing approval for continued membership, including the previous referendum in 1975. In fact, public opinion was never so overwhelmingly anti EU as in Thatcher's early premiership - yet she was the one who ensured continued membership then, while Labour opposed it, facts 'forgotten' by both parties now. Chart 1: public concern about EU over time Chart 2 views on leaving/remaining over time But British views on the EU were always more complex and nuanced that the binary choice, Leave/Remain.. In the 2015 edition of 'British social attitudes', John Curtice, doyenne of British pollsters, showed that while usually only a minority had been consistently clear that they really wanted to Leave come what may, many Remainers also had reservations about the EU, and wanted reform (I came into this category myself, see my post of 31 May 2016 ) (2) . Few were ever unreservedly pro EU, or fully accepted it as it was. But at the same time, polls show that many who were unkeen on the EU did value some things about it: the protection of workers' rights, free trade with the EU and free movement of Brits into the EU (but as we will see, what many people seemingly meant was a one-way street). So the British seemed to have a majority for reluctant acceptance that being in the EU was better than not, weighing up costs and benefits. But what they really wanted was a reformed EU, re-made in a way that suit them better. Of course, there were different views on what 'reformed' meant – something not adequately explored by Cameron, who seemed happy to take whatever was offered him and present it to the UK public as significant change. Curtice also showed that the British thought about the EU in 2 different ways : instrumentally I.e. in times of practical benefits and results (stronger among the middle classes who benefited most) and in terms of identity, such as cultural cohesion and owning 'control'. There was a ready feeling, egged on by right wing media, that the EU was intruding excessively into things that ought to be for the UK to decide on. Britons felt they wanted to be 'in Europe but not run by Europe', a phrase which seems to capture the majority pre-Referendum mood. That is borne out by the regular survey of public opinion in each EU country (3), which has always placed the UK towards the Euro-sceptic end of the spectrum, but especially as regards the possible expansion of the EU's role (e.g. a European army, common foreign and defence policy, full economic and monetary union). Similarly, Britons never shared Blair's enthusiasm for the Euro (a fate Brown saved us from, and deserves more credit for doing so.) The issue of identity became linked particularity to worries about immigration, which rose enormously after the mid 1990s, first from outside the EU and then later in the mid 2000s from within the EU (I wonder how far the public ever really distinguished the two?). The UK was far from alone on this, indeed in EU surveys some other countries reported greater concern than us on the issue, and in no less than 20 countries it was reported as the top public concern in the EU survey in 2015. But the UK was shown consistently least supportive of free movement within the EU and most likely to see control of immigration as issue for national Government, not the EU. Within UK politics, immigration was, by far, identified as a key issue by voters by the middle of this decade. On this reading, the refugee crisis of 2015, including Merkel's dramatic pronouncement of a massive numbers of which every country 'must' take its share, and scenes of violent chaos on the borders, was tailor-made to drive the UK to vote Leave. (If, as has been suggested, Russia worked with Assad deliberately to drive a million refugees in Europe's direction, his strategy was brilliantly successful.)(4) The result of these concerns about identity was that UKIP, which had done remarkably poorly in the 2010 (only 3% of the vote), began to gain traction. It came first in the European Parliamentary elections in 2014, they got 17% in the simultaneous local elections, and 2 Tory MPs defected. Cameron, to stave off UKIP inroads into Tory votes, offered the Referendum, misreading the polls which in headline terms still seemed favourable to Leave, but not detecting the shift in underlying attitudes from instrumental issues to issues of identity, or believing he could negotiate real concessions on migration. But in the end he secured remarkably little change, and none of substance on the key issue, migration. This distinction played into the campaign itself. Leave understood that the issue was identity and especially immigration: hence the appalling Leavers' lie, that Goebbels would have admired, that a million Turks were on our way here to rape your wives and daughters (5) While Remain utterly failed to run the instrumental argument that being in the EU (including migration from as well as to the rest of the EU) had given us great benefits. Mandelson describes the decision by the the Remain campaign not to explain what the open market meant, and how greatly it benefited us (6).- Instead, relying on warnings of catastrophe, which were simply not believed. The effect of this bitterly divisive campaign was to destroy the more nuanced, balanced understanding that had existed, and force everyone into one side or the other of a strictly binary choice. It also seemed to rule out the possibility, however remote, of 'reform' some time in the future. This polarisation is shown in real time by analysis by the British Election Survey of how, during the campaign, people began with increasing strength to identify with the community of Leavers or Remainers – and continued to do so after the vote. What is striking is that while the Leave group was more strongly cohesive at the start, Remainers became more so towatds the end - and their cohesivness, their feeling of being part of a beleagured community, intensified remarkably in the shock of defeat. The democratic process iself drove us apart. Chart 3: increasing polarisation during the Referendum campaign, and after  That was been my own experience. Before the Referendum, I was pretty Eurosceptic, that is to say, while I never really wanted to leave, I was aware of how dysfunctional the EU was (and is) and how incapable of reform. But the moment we were asked to vote whether we really, seriously wanted to leave, I had no doubt that leaving must mean a huge and permanent loss of wealth, and of influence in Europe and beyond. But more than that, it means mentally turning our backs on the world and turning back to the past.

The Campaign itself solidified my views. I met many Europeans while canvassing in Oxford, a great international city, and though how much I liked having them around, how much I had in common with them as they wished us luck; I met ardent Leavers whose reactionary values, contempt for foreigners, credulity for blatant lies and sheer wilful ignorance I found repugnant. At national level, too, the lies, hate-filled nationalism and outright racism of the Leave campaign appalled me. So I started by thinking instrumentally, but ended up putting more weight on identity: only my identity turned out not to be nationality. So that was what happened: a majority for a sceptical, nuanced , pragmatic acceptance of the EU was over- turned by botched handling of immigration by the EU, failure by Cameron to secure signifiant reform, by a vicious, xenophobic and racist campaign, and by the very nature of the Referendum itself, which forced us to take one side or the other, forced us all into our trenches, which we began to dig and reinforce against attack. And now the British people are terribly divided: polls show that remarkably few have changed their view since the vote, we comfort and support 'our' people in 'our' side and stare at the enemy lines through periscopes across 'no-mans land', which is where we used to live. The enemy is ourselves. Not the least poisonous aspect of this is the excruciatingly slow pace. If Brexit had been over and done within months, we might now be on our way to adjusting to it. But it moves glacier like. It will be years and year before we fully leave. And then years before we fully see and understand the consequences, economic, geopolitical, cultural, psychological, social. And in the meantime, all we will hear about, all we think about, is Brexit, Brexit, Brexit. Parliament itself is devoting the best part of 2 years to nothing but. And every twist and turn of the process injects remains us how right we are, how wrong they are. It This process will take the rest of my life. I will die to the tune of Brexit. So let us now all agree to curse the man who is principally to blame for this: David Cameron. Is there, in all our history, a Prime Minister who has done greater harm to this country? The man who played Russian roulette with this country's prosperity, influence and sense of community, for personal and party political advantage. And lost. The man who fired the first shot in the civil war that propelled us into our trenches. And is he now contrite? Well, here's what he had to say recently: “Obviously I regret the personal consequences for me. I loved being prime minister. I thought I was doing a reasonable job, But I think it was the right thing. The lack of a referendum was poisoning British politics and so I put that right.” (1) https://www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori/en-uk/economistipsos-mori-september-2014-issues-index?language_content_entity=en-uk (2) http://www.bsa.natcen.ac.uk/media/38972/bsa32_fullreport.pdf (3) http://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm (4) https://www.theguardian.com/media/2017/jun/29/where-is-the-space-in-the-guardian-for-traditional-values (5) http://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/nigel-farage-turkey-brexit-eu-referendum_uk_57234a8ae4b0d6f7bed5d801 also http://www.express.co.uk/news/uk/661387/Migrant-crisis-Nigel-Farage-Turkey-EU-visa-free-travel (6) See my post of 6.7.2016

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed