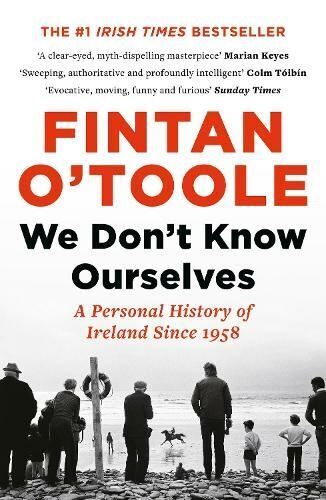

Review of Fintan O'Toole's "We don't know ourselves: a personal history of Ireland since 1958"8/1/2023 By the time I got about halfway through this book, I thought to myself: yes, it's ingenious ( the linking of stages in his own life to stages in modern Ireland's history), it’s very well written and it’s very informative - I knew most of the story in outline, but some things were new to me - the replacement of the old Protestant Ascendancy by a new ruling class after independence, the extent and brazeness openness of their corruption under Haughey, and the wild speculation of the Celtic Tiger years (all of which made me feel that Boris Johnson and Co had something to learn about corruption and speculation, after all). New to me also, the extent of Irish emigration in the late twentieth century. But, I wasn't enjoying the book at all. For the author seemed not merely to disapprove of much of what the Irish said or did, but actually to despise them. And on his account, that seemed a reasonable response to a society composed equal parts of mediaeval credulousness, obsequiousness to power, sentimental self-delusion and callous indifference to the sufferings of those most in need. It was like a novel where the author has, and generates in you, no interest in the fate of his characters. Why read on? What I lacked was a narrative - a way of understanding this story, that made it more than just one damned thing after another. And in the last quarter or so the book, everything changes - we get that narrative, we see Ireland change fundamentally, we understand why O’Toole has told the tale in the way that he has. His thesis, which seems compelling, is that the Irish were unable to think clearly about themselves, but took refuge either in evasion and duplicity - what he calls knowing but not knowing – or in grasping at versions of themselves that were however not true, or not wholly true. The last quarter of the book describes the destruction, largely self destruction as it turns out, of the things that were keeping the Irish from themselves, keeping them in confusion and in fear. Above all the destruction of the Catholic Church, as a result of exposure of its system of torture and slavery of children and women through the Christian Brothers, the Magdalen Laundries, the mother and baby homes, sexual predation by priests and routine cover-up by the heirarchy. And the overthrowing of oppressive Catholic sexual morality - which as he shows was largely in fact exercise in hypocrisy at the expense of the most vulnerable - through the unstoppable intrusion, first of American, then European culture, and finally the inrush of immigrants to Ireland from all over the world in recent decades (another thing I had not known). And in tandem with that, the weakening of the ruling class and the destruction of Fianna Fail, as their breath-taking corruption and economic mismanagement were so exposed that it could not longer be ‘known but not known’. Growing prosperity, and the ending of Ireland's traditional place as one of the poorest countries in the developed world. And finally the end of the old militant version of the nationalist dream, as a result of revulsion at the excesses of the IRA, at violence as an end in itself, of the gradual acceptance by the IRA that they could not win militarily, and of the the dawning realisation that hardly anyone in Ireland actually wanted a united Ireland brought about the extirpation and forcible driving out of the Prods, even if that were militarily possible. And that it might be possible, might even be better, to live with some ambiguity about the precise political expression of Irishness. Thus far, that might sound it was as simple as this: that Ireland had been very backward, and is now thoroughly modern. However he's making a much more subtle, interesting and I think more universally applicable point than that. He is describing a people, a country, which finally manages to see itself clearly, not by replacing one story by another, or by abandoning the past, or by becoming just like their neighbours, but rather by finding a way of living with uncertainty about its identity and about its future, instead of clutching at bogus identities and bogus beliefs. This is done in the fascinating final chapter where he rather wonderfully quotes Keats’ notebooks, of all things, on something he called ‘negative capability’: “capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact & reason” instead of being “incapable of remaining with half knowledge” (that’s Keats). Or O’Toole: ‘Ireland did not start as one fixed thing and end up as another…. It did not start out as isolated and become globalised.. it grew but it also allowed itself gradually, painfully and with relief to contract, to shrink away from the stories that were too big to match the scale of its intimate decencies. We ended up, not great, maybe not even especially good but......not so bad ourselves”. It's a beautiful conclusion. But one which is, for an Englishman, so full of anguish and almost unbearable pain. For we have chosen to go in the exact opposite direction. At the time of the London Olympics ceremony in 2012, it seemed for a moment that we might have passed peak Churchill, to have found a way of understanding our past in all its complexity without being a prisoner of it, and to welcome change and diversity even if we couldn't fully see where it was leading us. We seemed to accept all that … and then we didn't. In the Brexit vote, and subsequently, we decided, by such a tragically small majority, to concrete ourselves ever more firmly back into the past, or rather a highly skewed, essentially false view of the past. And in electing Boris Johnson, we opted for a kind of Fianna Fail ourselves - open, monstrous corruption, careless erosion of liberties and law, economic mismanagement on a devastating scale. Ireland has gone forward: we have gone backwards. And we chose it. We did it to ourselves. If there is any hope for us in this book, it is that the narrative which the new Tory party is spinning is self contradictory and already falling apart in front of our eyes. Leaving Europe did not make us more free or more prosperous but the reverse. Letting the rich make themselves much richer did not trickle down to the majority. Once uniquely poised between the US and Europe, able to mediate between the two, we are now a figure of ridicule or best pity internationally. Internally, we are more hypocritical, more at violently at odds with ourselves, more confused, more depairing than at anytime I can remember. All this contains the seeds of its own destruction. Sadly, we lack any politician capable of seeing that , of giving us a sense of hope, on left all right. And I am not wholly confident that will pull through. As I wrote after the Referendum, countries can lose their genius, can slide into terminal decline. But there is some reason for hope: polls show that the ghastly reaction we are living through is concentrated in my generation, and that the young are more radically minded that previous generations of their age. I think the time may come when we turn our back on the myths of English exceptionalism and have the courage to breakthrough, back to the real world, and to our own best instincts. But because we deliberately threw away our best chance, it will be very slow and very painful. And since my generation needs to die first, I won't be around to see it.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed