|

A persistent characteristic of criminal justice policy in this country is the commitment to rehabilitation: the belief that every offender has the potential to repent his/her ways, and that the criminal justice system should encourage and support that change. It is remarkable, and heartening, that this idea has survived the drift to right in UK politics, so that it is as entrenched on the right as on the left of the political spectrum. That tradition was revived, after a period of deep pessimism in criminology ('nothing works') by the Blair Government in 1997, and taken to a new level - a 'rehabilitation revolution', if you will. Labour's belief in the capacity of huge state programmes to shape and improve society took the form, in the criminal justice system, of a new approach to reducing re-offending:

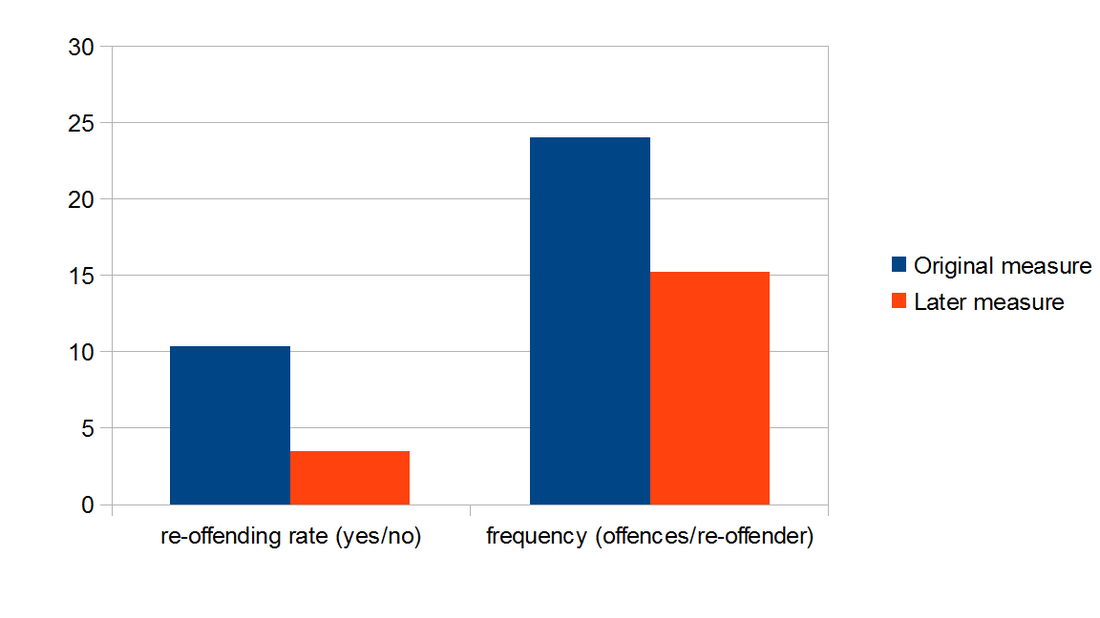

One might think that politicians since then who have so fervently declared their ambition to reduce re-offending would at least inquire what happened to the Labour programme. But I cannot recall any politician seriously inquiring into past efforts, at least for adult offenders. (Grayling's comment, in launching his probation changes, that there had been no progress in reducing re-offending rates prior to his arrival, was simply wrong, as I shall show.) Yet the data is there. What does it tell us? (I shall stick to adults for the moment because, God knows, that is complicated enough, and there are particular issues affecting juveniles.) Evaluation Measuring changes in human behaviour is complicated, and made more so by government's habit of changing the data definitions, and the way results are presented and explained, every few years. From the base year of 2000, changes in the way re-offending is measured have include: a switch from waiting two years from release from prisons (or start of community sentence), to measure how many are re-convicted to just on year; from measuring just whether they are re-convicted or not, to measuring changes in frequency and severity of re-offences; from measuring just convictions, to including cautions; from measuring using just the first quarter's data ,to using the data for the whole year; from expressing changes as percentage changes in the re-offending rate (thus, a fall from 50% to 48% was a 4% fall), to stating the change as percentage points (a 2 percentage point fall, on the same data). The results were shown two ways, as changes in raw data, and after adjustments to take account of changes in the mix of offenders which, other things be equal, would have made them more or less likely to offend. These changes sound terribly technical – but they do make a huge difference to the results: Chart 1: different results for % change in re-offending, 2000-09/10, using orginal and later measures Note: the fall in re-offending rate is here given as:

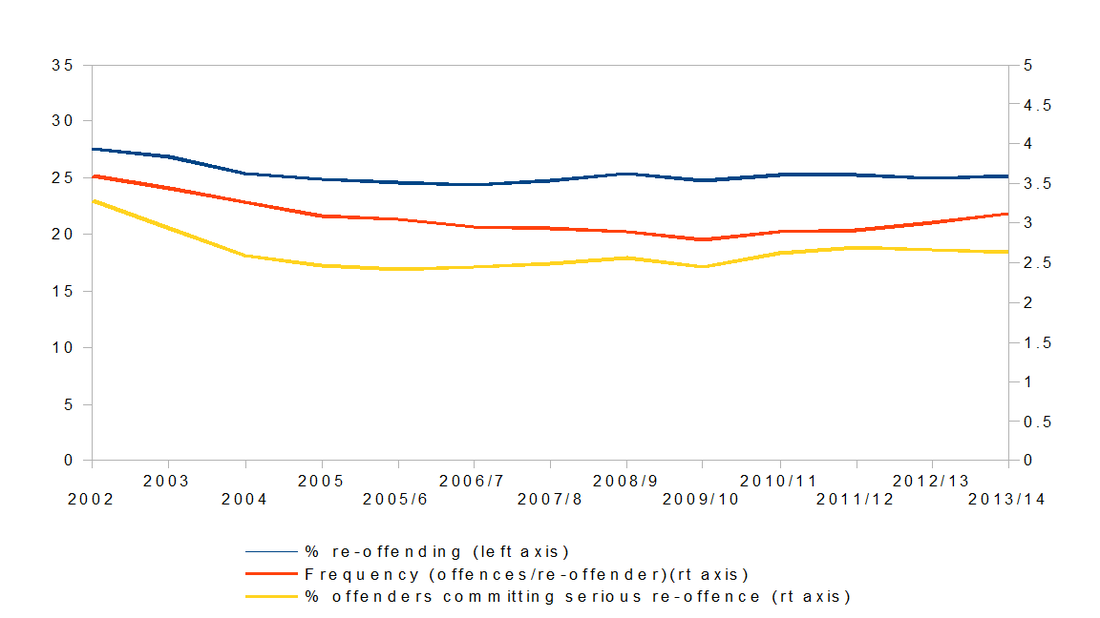

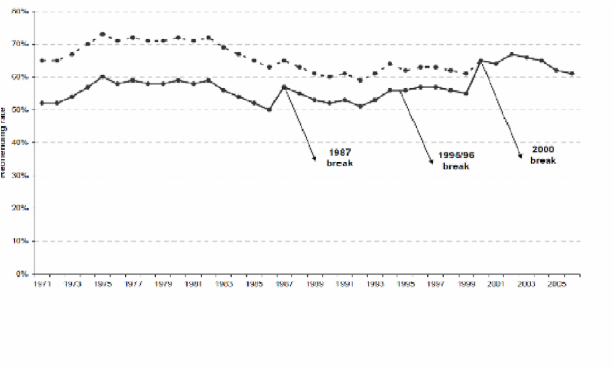

The lesson is that, as ever, you have to read the (very) small print on such statistics; and one should never assume they provide an absolute and unchallengeable truth about reality, as a thermometer or pressure gauge would. Nevertheless, the overall trend can be seen: Chart 2: Trend in re-offending rate, and frequency and seriousness of re-offending, 2000-13/14, adults, one year Note: 'raw' data i.e. not adjusted for changes in offender mix. After a rise at the start of the 2000s, re-offending rates, frequency of re-offending, and the seriousness of re-offences all fell in the mid 2000s. Since then, there has been no further fall. Was that reduction, though, a result of government action? After all, the re-offending rate fluctuates 'naturally' over time, for example over the quarter of a century before Labour came in in 1997: Chart 3: changes in re-offending rate at 2 years, 1971-2008 (The dotted line in this chart shows the rate adjusted for breaks in series.) What it shows is entirely counter-intuitive: that there was a sustained and significant re-conviction fall in re-conviction rates just at the very worst years of the prison crisis of the 1980s, and the period of 'nothing works' in criminology. (Or it could be an artefact of declining police detection rates?) At any rate, there is a case that the fall after 2000 was merely another natural fluctuation, and nothing to do with government policy. Yet that the reduction in table 2 was, at least in part, the result of the re-offending programmes is made plausible by the following:

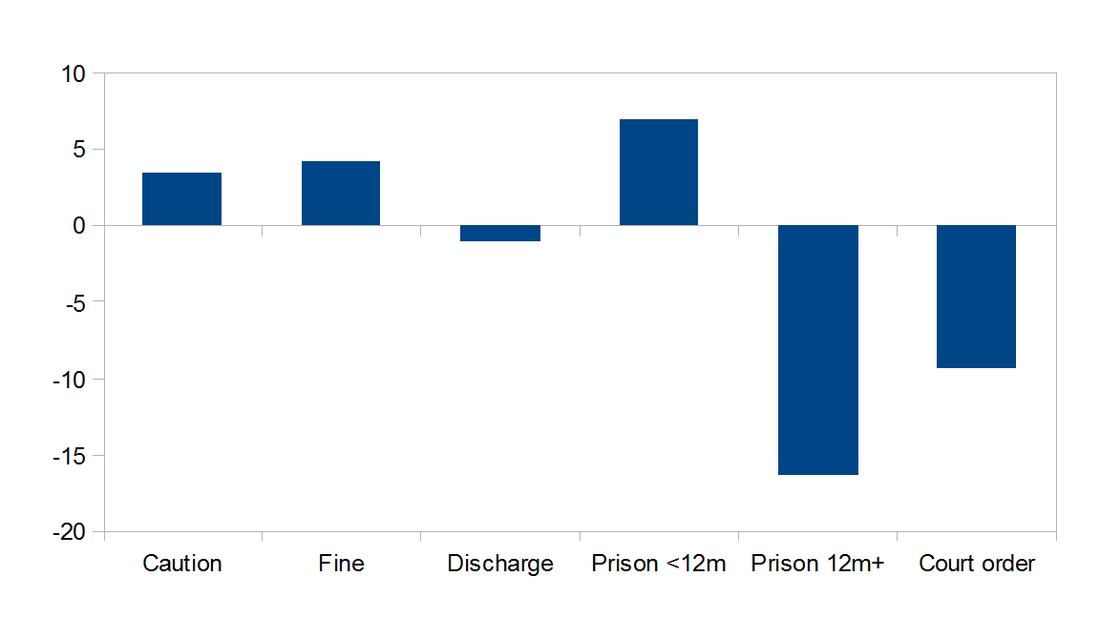

Chart 4: % changes in re-conviction rates, adults 2000-2011, by disposal Note

-these are % falls in the % rate -of those given a court order, most were supervised by the probation service, but not all (The reduction achieved with prisoners is extraordinary, and something the prison service has never received credit for. On the contrary, we get the old myth lazily repeated on the left and right, that prison fails to acheive anything positive.) It is possible to estimate roughly how many offences were 'avoided' i.e. would otherwise have occurred but for the reduction in offending, and frequency of offending. In 2010, that was about 80,000 a year (that is, offences resulting in conviction or caution - but many more, if those that were never reported to or solved by the police showed a similar fall). Not an insignificant number, I suggest, of people who did not become victims of crime. Costly, yes: on my recollection of the sums involved, around £3000-4000 per crime avoided. I leave it to you, and the economists, to decide if that was worth it. But it is a small fraction of what is spent convicting and punishing those who re-offending is not reduced. Conclusions

Implications for policy now The main implication is surely negative – that in current circumstances, there is no reason to believe that further reductions in re-offending rates can be achieved as a result of government action. Consider: the Blair programme had the benefit of hundreds of millions of new money; of staffing ratios were much more generous than today; of new knowledge of 'what works'; of sustained political will. Yet the fall it achieved was small. No other initiative has made any impact. Today, there is no prospect of new investment ever being affordable; or of any relaxation of record low staffing ratios and unprecedentedly tight budgets; or of any relief to overcrowding; and the increase in knowledge of what works since 2000 has not been game changing. Cuts since 2010 are thought (by everyone outside the MoJ) to be making prisons less safe, and less likely to succeed in reforming prisoners. As for probation, the Grayling experiment of throwing all the cards up in the air simultaneously means tremendous risk; for most offenders, resources are likely to reduce, not increase; cross institutional working must become more difficult as the probation service has been fragmented; while 'payment by results' has yet to be shown to work in reducing re-offending. The one exception is prisoners serving less than 12 months. As we've seen, they were the one group for whom re-offending rates did not improve, for the obvious reason that they were not supervised after release. If, as is intended, the CRCs release significant resources through greater efficiency, and if they choose to reinvest that in better preparation for release and post release supervision for short sentence prisoners, and if they use interventions based on research into what works, and if the benefit of those interventions outweigh the increasing stress on the prison system and prisoners – a lot of 'ifs'! – we should see improvement in re offending rates for that one group in 3 years or so. To be clear, I am not saying, give up on trying to reduce re-offending. Interventions do work for some, that is after all what the data shows: and prison and probation staff have a moral and professional duty to do their best for the person in front of them. What I am saying is that it is simply not credible for government to think that it can achieve significant further reduction in the re-offending rate, other than for short term prisoners. Of course, such reductions may occur naturally, as a result of general societal changes - and if they do, government will no doubt claim them as an achievement! One could go further and question whether, in the light of the amazing fall in crime since 1995, and the equally striking reduction in public concern about crime (demonstrated in opinion polls), seeking a reduction in the re-offending rate is quite the priority it was 20 years ago, compared to other long-standing problems in the criminal justice system, such as the absymally low detection rate or the slowness of the criminal process or the high rate of cracked trials. Or for that matter, demands on other hard pressed public services, such as the NHS or schools. A second implication is that poor prospects for further reducing re-offending should prompt re-thinking of criminal justice policy. If (as the statistics plainly show) for the majority of offenders no disposal will reduce their future offending, it follows that sentencing must to be based on other aims. Government should therefore start thinking again about the business of sentencing, which it hasn't done seriously now for a generation, and not by accident – it has been a politically willed absence of thought. Yet during that time, use of custody has doubled, with the enormous costs associated with it. I will return to that in another post. A last query, on which comments are welcome: given the general rate of offending has fallen so dramatically since the '90s, why has the rate of re-offending remained so stubbornly high? I assume the explananation is that fewer people now turn to crime, but those that do embark on criminal careers find them just as hard to get out of as they ever did. Or is there some other explanation?

8 Comments

David Barrie

11/4/2016 11:30:15 am

Very interesting - I hope you may have something to say about the effectiveness or otherwise of non-custodial sentences in reducing reoffending. Some such schemes really do seem to work (at a much lower cost than prison) but hard data are in short supply.

Reply

Julian Le Vay

11/4/2016 12:40:03 pm

David, thanks, As I'm sure you know, the great difficulty is in finding matched groups of offenders who get different sentences. Otherwise, comparing re-offending rates for community and prison sentences would be like comparing death rates for ops for in-growing toenails with those for heart surgery! MoJ did one such study

Reply

John Steele

16/4/2016 12:19:39 pm

Yes, a thought provoking piece. There are many reasons why the under-12 month custody reoffending rates are so high and lack of post custody supervision is one. But Grayling's reforms have not as far as I know resulted in any serious reinvestment in this aspect and I suspect that a lot of the (arguably unfunded) work with this group previously undertaken by Probation Trusts has been lost in the recent changes. Blair's Custody Plus legislation which was never implemented was a huge missed opportunity. With hindsight, it was the then current obsession with gold plated services that made it too expensive. Subsequently Grayling refused to consider an offer by Trust Chairs to take on the under 12 month cases with no extra resources. Probation Trusts have never received credit for their huge increase in productivity whilst maintaining, or improving standards, which made this offer possible

Reply

Julian Le Vay

17/4/2016 08:52:14 am

Thanks John."...not as far as I know resulted in any serious reinvestment in this aspect.." We'll never be allowed to know that, of course, as it is commercially secret, even though that shift of resources is the aim of Grayling's changes. We'll know if re-offending of that group goes up or down but not whether they re-invested and failed to make an impact, or couldnt get enough cash out of the existing operation or did but chose to take it as profit.. Commercially, you might make the judgement that the PBR element just wasn't worth what it would take to achieve it - the monetisation of care can have unintended effects.

Reply

Kathy Hampson

18/4/2016 08:47:42 am

You made a quick comment about preparation for release being important, which is also flagged by the research. However, prisons are all about what happens 'inside' rather than preparing for the 'outside'. This is all also true in my (youth justice) sector, where children given custody are not even offered a preparation for release course (in the preferred provision for North Wales - in England!). They are also, due to contractions in budgets causing a reduction in the number of sites with youth justice places, placed massively far from home, compounding any attempts to start resettlement work prior to release. The YOTs are all being cut to the bone, so surely progress in the youth justice sector is actually being confounded (by stealth) by the Government itself? Justification for plans post-Taylor review, I think!

Reply

Julian Le Vay

18/4/2016 09:32:01 am

I am about to post on Taylor. He proposes a high cost high quality solution - small custodial units all over the place, intensively staffed, all the right specialist support - as though the failure of the YJB to provide such was just a curious failure of judgement. Whereas, of course, small units were what the YJB always ideally wanted but just couldnt afford, even before the Crash, and even less so now. You also make a good point that even if Taylor units were affordable they'd do little good if the post release services arent adequate.

Reply

18/4/2016 09:47:10 am

Expecting our prisons to reduce reoffending is largely a blind alley for the Prison Service. Our prisons are not Hogwarts, prison officers are not Harry Potter, they carry batons not magic wands.

Reply

Julian Le Vay

18/4/2016 05:46:43 pm

Thanks Mark, that is heartfelt stuff and reminds us that all these figures and convoluted arguments are about real, difficult lives. Actually, I think the criminologists would pretty much agree with you: prison staff cant just 'change' people, as though waving a wand, but they can sometimes help those who really want to change to do so; and that it is only ever quite a small proportion of offenders who they can help successfully change the direction of their lives. But worth it, when it works.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed