|

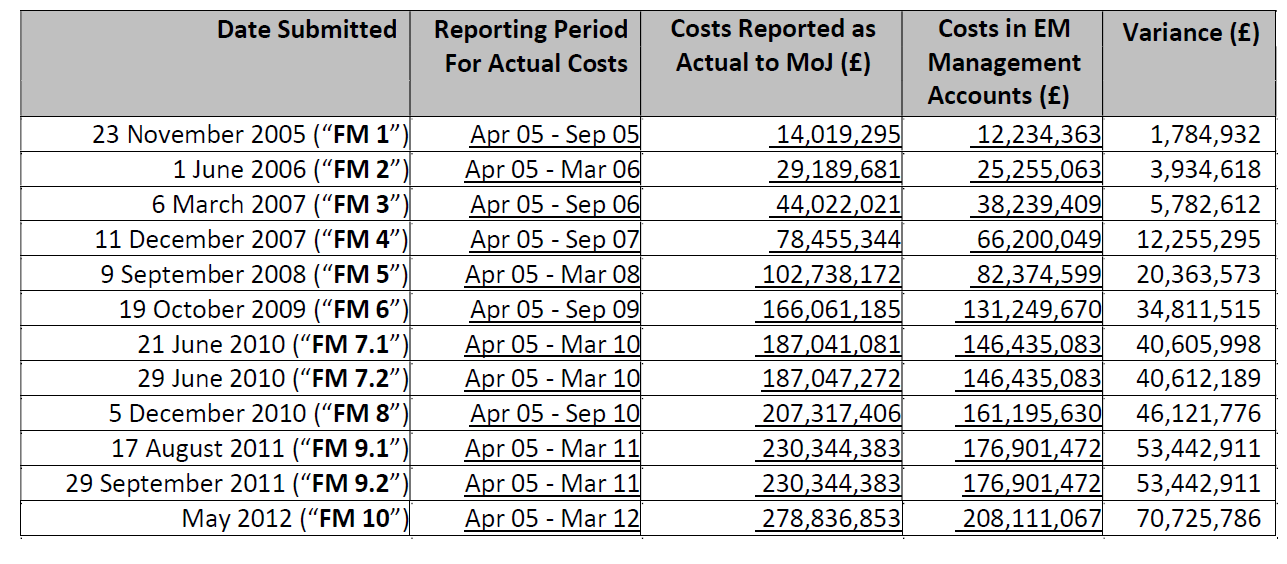

G4S has admitted a serious and sustained fraud again the public purse dating back to the early 2000s, in relation to its contract with the MoJ for electronic tagging of offeners. But in July this year, G4S was able to buy off prosecution for fraud, by paying £44m - a process called a Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA), which has to be signed off by a court and published. The judgement on the G4S DPA, here, (as in the similar one with SERCO last year, here,) reveals much not only about the criminality of G4S, but the contributory negligence of the MoJ as customer which enabled the fraud, and the extraordinary slowness and high cost of the Serious Fraud Office (SFO). It also casts doubt on whether the DPA was properly made in this case, and indeed, whether DPAs are even compatible with most peoples’ idea of ‘justice’. What are DPAs? DPAs were imported from the American judicial system by the Courts and Crime Act 2013. The background was the abysmal performance of the UK authorities in dealing with economic crime, highlighted by the financial crash of 2008. UK US. The SFO in particular was under fire, following collapse of yet another major trial (the Tchenguiz brothers), due to a series of very basic failures to follow procedure, and its own governance was questioned after an unauthorised pay off to top staff. This was the reasoning: prosecuting economic crime is difficult, slow, expensive and cases often collapse embarrassingly. A major obstacle is the legal doctrine of ‘directing mind’ which requires it to be shown that employees of the company committing the crime are in fact acting as the company. Also, detecting such crime in the first place and securing evidence is difficult, given the absence of any incentive for the company itself to own up or cooperate with the investigation. The idea of the DPA was that instead of prosecuting the company, the prosecuting authority would invite it to do a deal under which the company would recognise wrongdoing, cooperate fully, hand over all evidence, pay a financial penalty and implement under supervision measures to improve corporate governance. (A DPA only avoids prosecution of the company itself - individuals who worked for the company may still be charged and in a number of cases, have been.) Such arrangements are familiar in the USA, but the murkiness of deals done there behind closed doors worries British jurists. To answer such qualms, the DPA as introduced here has to be signed off by a court, and has to be published, while the rules governing its use are set out in a published Code. DPAs do not apply to individuals, and apply only to economic crime (not for example, environmental crimes). There has been widespread criticism of DPAs (though mainly by City law firms likely to be batting for the accused eg here). Much of it centres on the tension between avoiding prosecution of the company, while prosecuting individuals who worked for it. In the Rolls Royce, Tesco and Guralp cases, criminal prosecutions against former officers of the companies fell apart. Indeed, no individuals have ever been convicted of the wrongdoing that prompted the investigations which led to any of the DPAs. Critics say this leaves a conundrum that a company has publicly acknowledged very grave criminal offences and paid a lot of money by way of reparation, but seemingly no actual person was criminally guilty of any wrong doing. Shareholders ask why, then, so much of their money has been paid over – indeed in both the SRCO and G4S cases, shareholders threatened legal action against the company, in relation to the effect of the fraud on the share price, here and https://www.law360.com/articles/1236163/serco-shareholders-sue-over-stock-dive-after-fraud-probe. Other critics are concerned that individuals at risk are not properly protected during the company’s internal investigation, or in the disclosure of evidence to the SFO, are excluded from the negotiations with the SFO, and if acquitted, have no way of removing the taint implied in the DPA agreement, since it has alreayd been declared that the conduct was criminal, a case of 'verdict first, trial later'. There is concern that it may suit the SFO and company very well to throw a few individuals who may not have been the prime movers to the dogs – ‘look, there go the rotten apples, good riddance, problem solved’. A constant throughout the period is the glacial pace of SFO investigations and the high failure rate of its prosecutions. In fact, in 2017 the Tories made a manifesto commitment to abolish to SFO and hand over its functions to the National Crime Agency, but immediately dropped the idea on returning to power, proposing instead to rethink its whole approach to economic crime, a rethink that has continued ever since, if ‘think’ is the right word for a Government so adrift on every issue. Apparently the MoJ are too busy with Brexit to do much thinking. A recent Lords report again slammed the legendary slowness of the SFO here, while the SFO have quietly dropped a further slew of major investigations that have been underway for years (Rolls Royce, GSK), here. Successive heads of the SFO, and many commentators, have proposed to tackle the problem of proving a ‘directing mind’ by creating a new offence of ‘failure to prevent’ economic crime, such as already exists for bribery under s.7 of the Bribery Act 2010, which used this formula specifically to make it easier to prosecute without having to prove the ‘directing mind’ was at work. Instead, what would be at issue is whether the company had in place adequate procedures to stop the sort of criminality. In fact, an attempt to introduce the same concept to fraud was mooted during passage on the 2013 Act, but shot down by the Government. And the idea has now disappeared into the black hole that is of the MoJ. In any case some critics have doubted that this is the best solution here . Some argue that the 19th century legal doctrine of 'directing mind' is antiquated in an era of large, complex company structures and also needs to be undone. Curiously few have raised the moral question, whether it is actually right for the State to let big, wealthy companies buy off prosecution for very serious crimes, especially crimes against the State and the taxpayer. I return to that issue at the end of this article. Recap of the story so far There has never been - and will never be – any public inquiry, so many facts about the case aren’t known and may never be known. The National Audit Office reported on the issue in 2013, but because of the SFO investigation, could not take it very far. An internal MoJ investigation was started, but immediately dropped, for the same reason, and has never been proceeded with (see chapter 5 of my book). G4S has submitted a Statement of Facts to the SFO but of course, that will never be published. The sub judice rule is a great friend to those with embarrassing secrets to hide, above all, the MoJ itself. Thus, we are a long way from knowing the full story. We may hope that a deal more comes out when ex-officers of SERCO and G4S come to trial – if they get to court. The SFO’s inglorious history of cracked trials and cases dismissed does not inspire confidence. Briefly: electronic monitoring of offenders (‘tagging’) was introduced by the Home office (before this work moved to the MoJ) in the 1990s, and was contracted out from the start (it has never been done in-house). SERCO and G4S quickly became dominant players, sharing the tagging market between them. They also ran prisons, prisoner escorting services, youth custody and immigration custody, becoming ever more deeply entwined in our justice system. Between them they earn hundreds of millions a year from MoJ and the Home Office. MoJ has allowed a tri-oploy to develop for running prisons, Serco, G4S and Sodexo. So, the customer is highly dependent on these two companies, indeed the market in detention and correctional services would collapse without them. In July 2013 the then Justice Secretary, Chris Grayling, told a shocked Commons that in the course of preparing for re-tendering of the contracts, his Department had uncovered serious over-charging by SERCO and G4S going back some years. The matter was referred to the SFO. Here we are, a mere 7 years later, with a decision not to prosecute the company. What this DPA reveals On 17 July Mr Justice Davis signed off the DPA between the Serious Fraud Office and G4S, under which the SFO agreed not to prosecute G4S for defrauding the Ministry of Justice, in return for G4’s payment of £44m and commitment to various improvements in its corporate governance. The same judge signed off a similar deal with SERCO a year ago. What this document reveals is extraordinary and deserves wider circulation. 1) G4S charged millions for work it didn’t do. But this was entirely legal! At the time the scandal broke, it appeared that it consisted of G4S (and SERCO) submitting invoices to the MoJ and being paid for them, for work which the company knew perfectly well had not been done. Thus the Justice Secretary to the House: “It included charges for people who were back in prison and had had their tags removed, people who had left the country, and those who had never been tagged in the first place but who had instead been returned to court. There are a small number of cases where charging continued for a period when the subject was known to have died. In some instances, charging continued for a period of many months and indeed years after active monitoring had ceased.” This was the assumption in the National Audit Office report in 2013, which detailed some of the ways this was done. For example, they would continue to charge even if they knew perfectly well the offender had absconded, if there were no order to cease – even though of course they knew they were no longer supplying the service charged for. They would continue to charge even after failing to install the tag successfully, so they knew they were not providing a service. Yet in July, the court declared that this was not fraud. Why not? First because the MoJ changed the contracts in a way that invited such conduct. As described in my book, there had been a problem that in the case of those tagged on remand, the date for cessation was the date fixed by the court for reappearance. But in practice, that merely lead to another period on remand. In the meantime, the contractors might have removed the tag, thus necessitating another home visit to re-install it. It appears – this is among the murky secrets never now to be divulged – that the MoJ responded by altering the contract, so that no expiry date was set, on the assumption that the court would order cessation when they finally committed the defendant for trial or discharged him. (The operators inserted their own expiry dates – SERCO set theirs as….the year 3000. Talk about a long-term income stream!) But predictably, courts didn’t bother to cancel orders, not having much interest in that side of things. Consequently, orders remained in force even though the offender might be at liberty or back in jail or even dead. The operators knew this. But they carried on milking the MoJ. It was an act of appalling dishonesty. But not it seems unlawful. It appears that such dishonest practices constituted most of the £180m which the companies paid back under duress in 2014 once they’d been found out. (Though just what that £180m comprised is yet another truth that will never be told, but in the case of G4S, some payments relate to other contracts where over-charging had been discovered, here: so this wasn't an isloated case). 2) Because the companies told the MoJ what they were doing. And the MoJ did nothing. The NAO report (2013) states: “G4S has stated to us that…the Ministry should have been aware of the way in which it was billing, and that it provided written explanations to the Ministry in 2009 that reflected its interpretation of the contract…” and “SERCO has stated to us that it charged in line with its genuine interpretation of the contract and that it was open about this to the Ministry throughout…”. That much was stated by the Justice Secretary in announcing the discovery of the fraud to Parliament in 2013: “The audit also reveals that contract managers in the Ministry of Justice discovered some of the issues around billing practices following a routine inspection in 2008. Although it appears that these contract managers had only a limited idea of the scope and scale of the problem, nothing substantive was done at that time to address the issues. None of that, however, justifies the billing practices followed by the suppliers.…..The House will … be surprised and disappointed, as was I, to learn that staff in the Ministry of Justice were aware of a potential problem and yet did not take adequate steps to address it.” That, I believe, is what made charges of fraud impossible, in relation to charges raised for work not done. Because the companies told the customer what it was doing. And the customer, it appears, did nothing whatsoever about it. 3) What was illegal was G4S’s falsification of financial reports, over a decade, to conceal excessive profits which it was legally required to share with the taxpayer When the first-generation of tagging contracts were due for re-tender in 2003, the Home Office (then the customer) was concerned that volumes and thus sending was rising. In an operation of this kind, some costs are more or less fixed whatever the volumes, other costs may rise, but not in direct proportion to rising volumes. Therefore, unit costs should fall. So, the Home Office asked bidders to disclose their true costs, so as to guard again excess profits. Each company was required, by the contract, to state annually its true margin to date, and expected future margin. The contract provided that if excess profits developed with rising volumes, the contractor must disclose these and so that the price could be adjusted. The contract required the companies to ensure these returns were ‘true and accurate’. From the start, before the contract even started, G4S lied its head off, sending in false returns that concealed its true costs and profit. It continued lying until found out. This schedule, from the judgement on the DPA, helpfully sets out the difference between the profit as disclosed to the Ministry, and the true position. 4) Even so, it was obvious that excess profits were being made, exactly as the MoJ had feared – but again, they did nothing

The customer had started the contractual process by stating its concern that the cost should not rise in direct proportion to rising volumes, but that ‘efficiency gains’ should be declared and shared with the MoJ. It was obvious, year after year, that the costs were rising in proportion to volumes (see my graph here https://www.julianlevay.com/articles/a-curious-graph ).But apparently officials did nothing to probe this, nor to ask how it was that G4S’s costs were rising in line with volumes. It is almost as if the MoJ had lost interest in the existing contracts as they prepared to re-compete them (indeed in cross examination later by the Public Accounts Committee, the then Permanent Secretary admitted as much (my book, chapter 5, footnote 13.) 5) The SFO took seven years and £6m to reach their decision not to prosecute G4S The scandal broke in 2013. It has taken the SFO 7 years to decide not to prosecute G4S. Granted the SFO is a by-word for sloth and incompetence, this is extraordinary. A year longer than World War Two. What were these people doing? After all this was not a complex case: only one company; only one customer; only one contract; no foreign jurisdictions involved, no fugitive suspects. Nor is this so unusual. In July 2018, the SFO disclosed that of cases currently under investigation, half had already been under investigation for more than 4 years (answer to my FoI request). Last month, 3 G4S executives were charged with fraud, 7 years after the case was referred to them. Does this extraordinary sloth matter? It does. ‘Justice delayed is justice denied’. Whatever one thinks of them, it is unpardonably oppressive to leave the G4S staff in question, and their families, and maybe others, under threat of serious charges for 7 years – 7 years during which they must have found it near impossible to get work in that sector. Such delay also means that memories will have decayed and that may cause evidential problems in court. It also means that for 7 years, Government has been awarding more contracts to an organisation facing trial for fraud against the Government. If the charges against individuals proceed to trial, it is unlikely that this saga will conclude before 2023, and if there are then appeals, 2024 or 2025 – more than two decades after the fraud started and a decade or more after the SFO started work. This is ludicrous, incompetent and oppressive, in such a straightforward case. 6) In secret, the MoJ lobbied against prosecution Bear in mind, what follows was all done in secret. The only reason we know about it, is that it was disclosed by the judge. Mr Justice Davis states the SERCO DPA last year that “the SFO has argued that the public interest would not be served by [SERCO] being debarred from participating in any government procurement exercise…This would be the consequence…were there to be a conviction, whereas it might not follow in the event of a DPA being approved”. This clearly can only have come from the MoJ. And in the G4S case, Mr Justice Davis quotes a statement by the MoJ’s Chief Commercial Officer’s saying that exclusion of G4S would have a of the ‘detrimental effect’ on the market for justice services. It is difficult to see these interventions other than as an argument against prosecution of the companies. Why else make them? In practice, the Judge worked out that in reality, exclusion of the companies from procurement following criminal conviction under the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 is not mandatory but discretionary – and Cabinet Office told the court that conviction would not necessarily result in such disbarment. So it is not clear that the MoJ’s intervention was even relevant. Nevertheless, the fact of MoJ’s intervention is telling. Not least because it is the MoJ itself which is responsible for its high degree of dependency on these 2 companies, so much so that even in the case of sustained and admitted fraud against the public purse, the MoJ cannot sustain competition without them. When I was FD of the Prison Service, we reckoned that to sustain effective competition for prisons we needed 4 established competitors. That was achieved. Then in 2008 a merger redirected that to three. Since then, the MoJ has repeatedly invited other companies – MITIE, MTC and others – to bid, and repeatedly awarded those contracts to the Big Three. The tri-opoly is the MoJ’s own doing. Result: SERCO and G4S are now it seems ‘too big to prosecute’. Government and outsourcers have become co-dependent. 7) This DPA does not fit the criteria laid down, and should never have been made In this case, the 'identification principle' was satisfied ie the doctrine of a 'directing mind' was not an obstacle to charging the company. There was a choice - to charge or not. So how was the decision made not to charge? The 2013 Act introducing DPAs provided for a Code of Conduct to be issued governing their use. That Code sets as factors relevant to the choice between a DPA and prosecution:

The Judge listed as factors tending towards prosecution:

In short, much of the case against prosecution of G4S seems ill-founded, if not downright perverse. There is a further and more basic point: the interests of justice. The Judge concluded that the DPA rather than prosecution was ‘in the interests justice’. Why? Because G4S had admitted criminal behaviour, repented, paid back its gains and undergone ‘cleansing’. He argued that ‘this will protect the public…in a manner more effective than any prosecution…’ He also argued that ‘the absence of a conviction will not affect substantially any damage to the substantially reputation of the company’. That statement is nonsense. The conviction of G4S for fraud against the UK Government would have had a devastating effect on its reputation here and around the world, indeed the ability of governments, including even this one, giving it contracts. As a sanction, the fine is irrelevant. Half a per cent of turnover. It’s nothing. And one of the fundamental objections to this DPA is that for the people of this country there is a huge difference between paying bribes to secure contracts abroad, in countries where bribery may be common, even an accepted way of doing business, even essential if you want to do business, and systematically stealing money from the British taxpayer. All the more so, since these people were trusted to supply vital public services. This should have weighted the decision towards prosecution. In my view, G4S ought to have been prosecuted. That, I am quite sure, would have protected the British public in a manner more effective than this glorified probation order. 8) DPAs are a conspiracy of the powerful and rich against the public good I return now to the nature of DPAs themselves. I have explained why they were introduced. The primary reason is that companies are difficult to prosecute for fraud, and the primary reason for that (apart from the incompetence and dilatoriness of the SFO) seems to be the legal doctrine of ‘directing mind’. The solution to these problems is not to avoid prosecution, but to make prosecution possible. First, as so many observers have argued, to import the ‘failure to prevent’ device into the law on fraud. Second, to modify or do away with the outdated doctrine on ‘controlling mind’ (which seems to be a British peculiarity and doesn’t exist in the US). Third, to replace the SFO which has failed so many times over decades to do its job promptly or competently. As I noted, few commentators have asked the most obvious of questions about DPAs: why is it right for huge rich companies to be able to buy off prosecution, while you and I cannot? True, we may be offered a caution, if we admit an offence and make restitution: but with this difference: it’s only available for the most minor offences. Not for stealing millions. Here’s why I think DPAs are immoral and unjust. It’s from court results in my local paper: LUKE *****, 34, of Banbury Road, Oxford, admitted stealing alcohol valued at £41 from Sainsbury’s, Oxford, on April 29. He must pay compensation of £41. Luke has been convicted of a very minor crime indeed, and has paid compensation, but also now has a criminal record. Why haven’t G4S and SERCO, who stole many million times as much? Are they just too big, too rich, too powerful to be prosecuted? 9) There never has been any inquiry into the negligence of the MoJ which enabled this fraud As I’ve noted, the effect of he unbelievably protracted SFO investigation is that the MoJ terminated its disciplinary inquiry into the seeming malfeasance of its officials who apparently knew the G4S and SERCO were charging for work done but did nothing about it (and did not tell Ministers). Nor any investigation of those charged with monitoring contracts who failed to react to the fact that tagging volumes were soaring but unit costs not falling, exactly what MoJ was concerned to avoid. Nor of those who changed the contract to remove the mechanism which stopped orders continuing indefinitely, yet took no steps to guard against the abuse that they had made possible. Ah yes: those responsible have ‘moved on’. Tell me, why is that always a defence for officials (and their ministers) but not for those now charged in G4S and SERCO? 10) We will never know the full facts The NAO investigation in 2013 was very limited by the sub judice rules (and did not in fact spot the real substance of the fraud at all). It cannot resume because of the cases now coming before the court. By 2022, it will all be forgotten. So, we will never know the full facts. And if those cases fold, we wont even know much about what went on inside G4S and SERCO. Of course, the SFO know, and the MoJ know – it's just you and me (and Parliament) who mustn’t know.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed