|

JUSTICE COMMITTEE INQUIRY INTO PRISON REFORM, SESSION 2016-17 EVIDENCE SUBMITTED BY JULIAN LE VAY Introduction I was Finance Director of the Prison Service between 1997 and 2001, responsible for contracts with the private sector. I was then briefly Director of Competition and Commissioning for the National Offender Management Services (NOMS). I later worked with two outsourcing companies on bids for (amongst other things) prisons, one in competition against the public sector, the other in collaboration with the public sector. I am now fully retired. My book, 'Competition for prisons: public or private?', was published by The Policy Press last year. This submission focuses on two issues: competition for prisons (and services within prisons); and the 'reform prison' concept. Mr Gove's statements on reform prisons made almost no reference to privately run prisons. This is surprising, on two grounds. First, when the Conservative Government introduced privately run prisons in the early '90s, the benefits claimed were precisely those now claimed for reform prisons: freedom from detailed central control, innovative practice, better value for money, better performance. It is surely relevant whether privately run prisons, which have now existed for a quarter of a century, have in fact achieved those benefits: and if they have not, why should reform prisons be expected to? Second, it is unclear what the relationship is meant to be between privately run prisons, and reform prisons. Would they run in parallel? Would one replace the other? The issue is especially pressing, because Mr Grayling as Justice Secretary suspended all competition for running prisons, and since then it has been unclear whether Government wishes end competition or not. Decisions need to be taken soon, in relation not only to the 9 new prisons announced last year, but also the ending of the PFI contracts, beginning early next decade. In this paper, I summarise what competition has and has not achieved, and argue the case for resuming competition, but better managed than in the past; and I make the case for a more pragmatic, evolutionary approach to devolution of powers to Governors than the 'radical autonomy' model proposed by Mr Gove. THE LESSONS OF COMPETITION TO DATE 25 years of competition The 14 existing privately run prisons have been procured in 3 ways:

Privately run prisons hold around 18% of the prison population in England and Wales. In parallel, specialised services within prisons have progressively been contracted out. Budgets and contracts for education and health moved to the Department for Education and Skills and Department of Health respectively in the early 2000s, and contracts were then awarded to specialist providers for each prison, or groups of prisons. Mr Grayling introduced centrally negotiated contracts for FM and resettlement services in all prisons, including (it appears) some or all of the privately run ones. This means Governors (and private sector Directors) do not control important parts of their prisons' operation, or even manage the contracts for them. The impact of competition Remarkably, Government has carried out no comparison of the cost and performance of public and private sector prisons since 2000 (and then only for the minority of 'non-PFI' prisons). And there has never been any full review of the working of competition and its overall impact. Research by the Institute of Criminology at Cambridge earlier in this decade produced important new insights about differences between sectors (and also within the private sector), but was limited to a few prisons and has been overtaken by changes, particularly steep cuts in staffing in both sectors, which have changed the picture radically (1). In my book, I look at all available evidence and conclude:

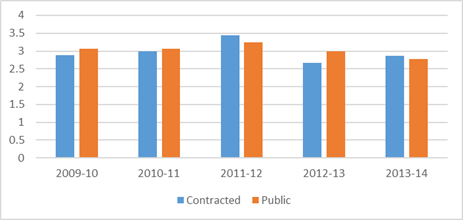

Figure 1 NOMS performance ratings of all prisons, by year Reproduced from my book, ‘Competition for prisons: public or private’ (2015)  Notes: 1 Prisons are rated annually: 4: exceptional performance 3: meeting majority of targets 2: overall performance of concern or 1: overall performance of serious concern. 2 Table excludes types of prison not operated by private sector (open, high security). 3 Table excludes contracted prisons which were in comparator groups which did not include any public sector prisons. Management of competition On the plus side:

But there are ways in which competition has not been well managed:

The end of competition? Mr Grayling abandoned competition, aborting the market testing then underway. He did a deal with the public sector: they drove down costs across the whole system through direct management at a faster pace than (though not as far as) was possible through competitions for each individual prison, by reducing staffing in public sector prisons, and contracting out support services in all prisons. (Thus, competition would have delivered bigger savings, but much more slowly, and time was of the essence to meet budget cuts.) In return, he suspended all forms of competition indefinitely. At the time of writing, there is no policy on competition and no decision on whether the new prisons announced last year will be competed at all, and if so, how. In my book, I consider the proposition that, following staffing reductions in the public sector, revised pay structures and pension arrangements, and estate rationalisation, there is now no significant cost difference between public and private sectors. Absence of published data on a comparable basis makes this is very problematic. For example, historically, costs of publicly run prisons have excluded costs of health and education contracts, which have sometimes been included in private sector prison costs, likewise differences in costs of insurance and risk transfer are not factored into published data. I concluded the private sector is still substantially cheaper:

Recommendations Competition is clearly in the public interest, and should be sustained. But it needs to be understood that competition is dynamic: it is not simply a question of whether one sector being better or cheaper than the other at a moment in time. Rather, monopoly power inherently tends to complacency, inefficiency and poor service - and the Prison Service’s record when last a monopoly shows this in spades. So it is desirable that providers should be aware that they can lose business - and that Government should be able to change providers. We should be clear what it can and cannot achieve. Competition, from where we are now, will not be transformative: its major impact has been realised already. But it will exert continuing pressure against rising costs and slipping performance, and inhibit a slide back into monopolistic behaviour. For competition to work well, and in the public interest, changes are needed in the way it is managed:

(1) Crewe, B. et.al. (2011) 'Staff culture, use of authority and prisoner quality of life in public and private sector prisons', Australian and New Zealand Jo. Of Criminology, 44 (1). Last year the same team published an intriguing study of the transition of Birmingham Prison from public to private sector, showing a significant improvement in prisoner quality of life: Liebling, A. et. al, 'Birmingham prison: the transition from public to private sector and its impact on staff and prisoner quality of life - a three-year study', NOMS (2015) 'REFORM PRISONS' THE CASE FOR A MORE EVOLUTIONARY APPROACH The Lord Chancellor's pause for thought on 'reform prisons' is welcome. Her predecessor's proposal lacked detail, took scant account of evidence and experience and its benefits were asserted, not argued. In particular, the following are relevant:

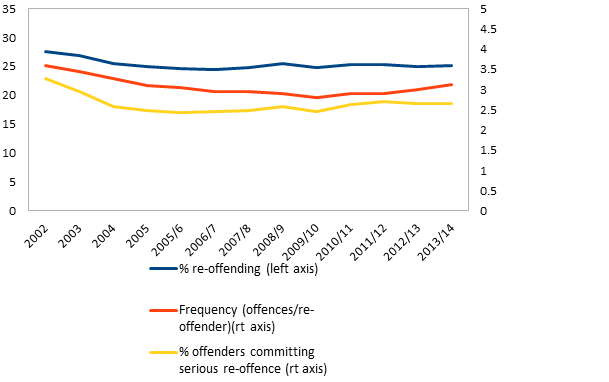

Figure 2: reduction in adult re-offending under Labour Government, 2002-2010 Source: MoJ re-offending statistics

All this suggests the following critique of the 'radical autonomy' concept (by this I mean prisons as semi-autonomous statutory bodies, with wide freedom from central control, on the Academy model for schools).

Centralisation and decentralisation often moves in cycles, and there is a good case now for more devolution, after unprecedented centralisation. Governors know their jails best, sometimes need to react quickly and after all, they are accountable for performance. But it should be pursued pragmatically: what, exactly, would make a difference? And does it really require an entirely different operating model, and a new statutory framework? What Governors often mention is exasperation with slow central recruitment, the need for flexibility to pay more for hard-to-fill posts, the imaginative use of small-scale ITC by privately run prisons and inflexible centrally run contracts for services in prisons. Some of this could be achieved without major organisational change, through devolution or improving central services. 2. But there are limitations, including cost But not all these functions can sensibly be devolved to every prison. There is an argument for more local pay flexibility (because local labour markets differ), but it would be inflationary (pay for some posts and in some areas would go up, but where pay is more than the local labour market requires, it would not be reduced). Staff movement between prisons could be affected. Opt out from central contracts would raise costs. All prisons require similar supplies and services – energy, food, clothing etc. These must be cheaper if purchasing power from over 100 sites is aggregated. Central contracts for FM and rehabilitative services have only just been put in place and can't now be cancelled. Savings made by providing common services would be undone if prisons opt out. Back office functions have been centralised to cut overheads. Re-creating local expertise on procurement, ITC and HR, essential to the ‘radical autonomy’ model, would be very costly. The prison system is a national one. Prisoners must move between prisons, which would be difficult if programmes and privileges differed widely; and big differences in treatment would be inequitable, could hinder preparation for release, and might be open to legal challenge. 3. It is very unlikely that 'radical autonomy' would transform performance Improved performance and less re-offending through innovation were benefits that the Conservative Government in the early '90s said would flow from privately run prisons. But they have not outperformed publicly run ones. They have innovated, but mainly on staffing levels and pay, and construction times and cost (described in my other paper) - and the public sector has already adopted much of this. More innovative use of ITC has been useful but has not transformed performance. This seems consistent with experience of private prisons abroad. Scope for innovation is inherently limited by constraints of prison routines, objections to wholesale substitution of ITC for human contact, and risk. On re-offending, the Labour Government's programme showed that even with several hundreds of millions a year extra funding and close attention to then new research evidence of 'what works', gains though worthwhile, were at the margins, and that is consistent with what the evidence suggested should be achievable. The results of the PBR pilots at Peterborough and Doncaster also showed only modest gain. Now, with no new money, much tighter staffing and not much new research evidence, and with rehabilitation programmes recently contracted out on long term contracts, there is no reason to think that big step reductions are achievable. (Not an argument for giving up, indeed there are other approaches that could be tried: but an argument against massive organisational change based on belief that a step reduction in re-offending would result.) 4. Accountability and control It is unclear that ‘radical autonomy’ would be compatible with proper accountability. The model is borrowed from the NHS and schools; in both cases, user choice is a theoretical mechanism for improvement, but this hardly applies in prisons! Hospitals and schools were never subject to the same high degree of ministerial accountability as prisons. When things go badly wrong in prisons, prompt intervention is needed, and the public expect Government to take responsibility: Mr Howard's efforts in 1994-95 to distance 'policy' from ‘operations' ought to be present in our minds. Moreover, the improved performance of prisons in the 2000s was due to increased central control, so that potential problems were spotted ahead of time, and the centre intervened before they materialised. That is not compatible with a 'radical autonomy' model where you wait to see what performance governors can achieve and impliedly, only intervene if things go badly wrong. For Governors, the 'radical autonomy' model might offer the worst of both worlds, where they publicly carry the can for decisions made centrally (on penal policy, funding, pay and central contracts). 5. Other solutions may be more relevant to current problems and more productive Most informed observers see the main causes of current problems as too many prisoners, too few staff and initiative overload, along with new drugs. 'Radical autonomy' will help with none of them. We have not had intelligent, informed discussion of sentencing for a very long time, rather, a willed absence of penal policy (and absence of policy is of course itself a policy choice). We have doubled the prison population since the mid '90s, at vast cost, yet in the same period, crime has halved: surely some serious examination of what exactly we have got for all that money is long overdue? (It is clear that this was not cause and effect – that the fall in crime was not achieved by increasing the prison population). Ministers tend to under-estimate the cost of major reorganisation, not least in terms of diversion of management effort and focus (and change overload has clearly contributed to operational problems in recent years). Another bout of wholesale organisational change would be unhelpful. On cutting re-offending, other options might be as or more effective, such as ‘half-way houses’ – or just increasing funding for resettlement services that are known to be effective. Conclusion Increased devolution to Governors is desirable, but should be pragmatically developed and implemented within existing structures. It is unlikely to transform performance. Other approaches could address current problems more effectively.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed