|

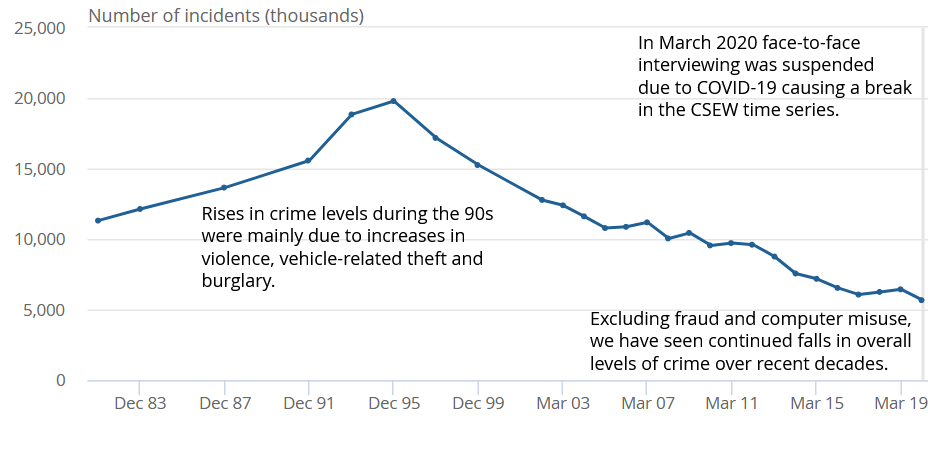

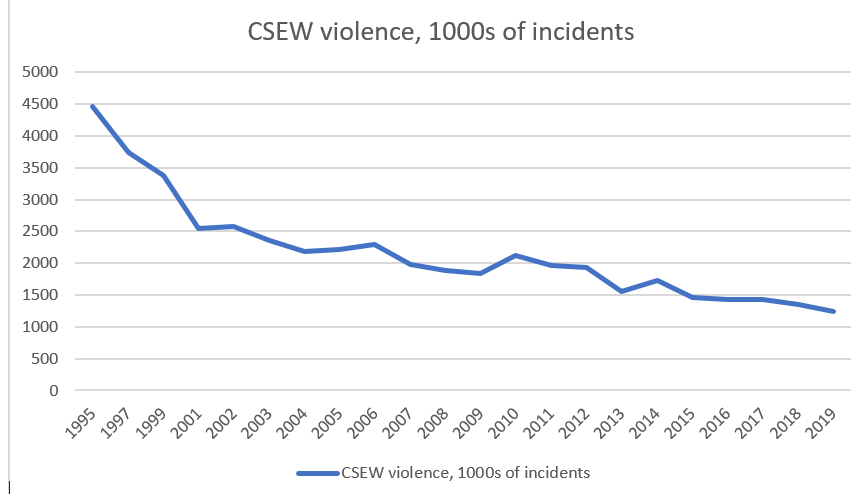

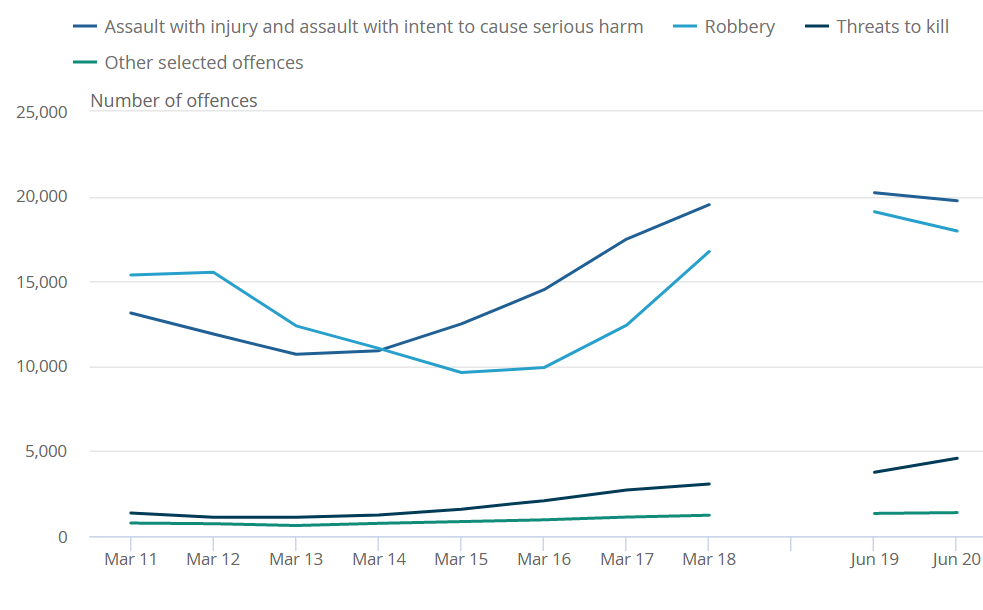

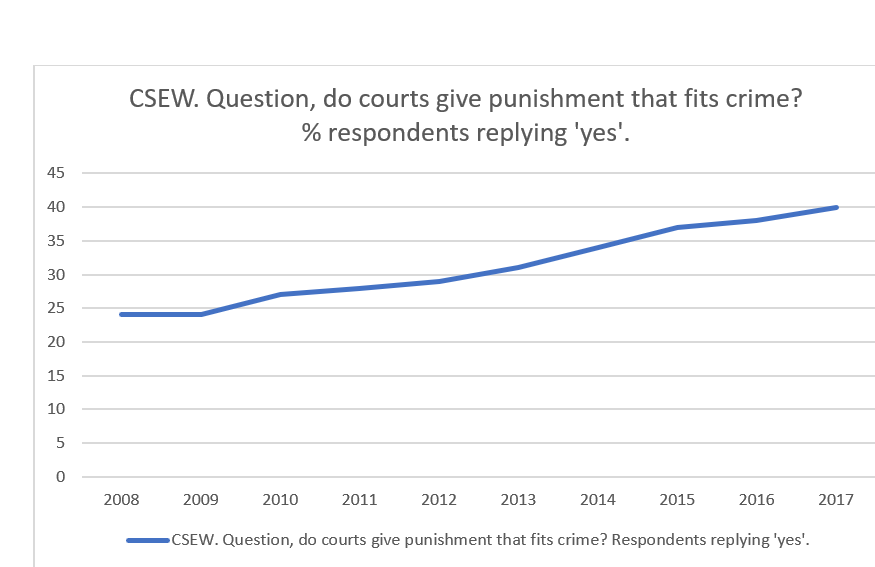

On 15 and 16 March, the House of Commons debated the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. The Bill will increase time served for ‘serious’ crimes and contribute to Government policies which are forecast to increase the prison population, already proportionately the highest of any major European country, to nearly 100,000. This will necessitate a huge prison building programme. Each cell costs a quarter of a million pounds to build, enough to build a family home. These sentencing policies are built on a series of untruths. What is so extraordinary is that each of these untruths is refuted by statistics which Government itself produces and, in one case, by the Minister responsible for sentencing policy himself. We are faced with rising crime Crime has fallen stupendously, almost unbelievably, since the mid-1990s (as it has done in other countries also). Regular surveys of victims show that violent crime, as experienced by the public, is down nearly 75% over the past quarter of a century. Crime estimates by the CSEW 1981 to 2020 Violent crime is no exception. It too has fallen dramatically. Some particular types of violent crime, like knife crime, have risen - but are now falling again, to around the level of a decade ago; and the numbers are small, and the crime highly localised. Sexual assault is decreasing. Conclusion: our streets are safer than they have been for several generations. This huge fall in crime is unprecedented for hundreds of years. But we apparently cannot bear to recognise it. We prefer to be afraid. Longer sentences will cut crime “Harsher sentencing tends to be associated with limited or no general deterrent effect. Increases in the certainty of apprehension and punishment have consistently been found to have a deterrent effect.” Typical left criminologist, eh? No. Actually, it’s Chris Philp, the minister responsible for sentencing police, answering a recent Question. Correctly summarising decades of criminological research. Days before his own policies for harsher sentencing were introduced in the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. What better illustration of our strange post-truth, post-reason, post-shame politics. See also here. Longer sentences are needed to restore public confidence The public have lost confidence in the courts to punish crime effectively, says the Government. Except, no. they haven’t. The contrary, in fact: for a decade, now, the public have steadily become more confident that the courts are fitting punishment to the crime. Prison can be an effective way of rehabilitating offenders

Well, it isn’t and never has been, despite the avowed intent of every Home Secretary or Justice Secretary for the past quarter century that it should be, and the investment of hundreds of millions in programmes to do so, based on the best what works evidence, and this when the system was under far less pressure than today. More here, and here. In fact there is recent research that the more unsafe prisons are, the less good they are at cutting reoffending. And they have become far less safe since 2010 (1). So, to summarise: the case against longer sentences is solid, well founded in easily available evidence. Almost no one mentioned any of this in the debate on 15/16 March. Instead, MPs queued up to say what a brilliant idea it is to increase sentences still further. No surprise on the Tory benches, now purged of the great tradition of Liberal Toryism. Bob Neil, who as chair of the Justice Committee certainly knows better, went along with this orgy of punitiveness. He is not one to raise his head aboe the parapet. No Ken Clarke, he! Labour continued its long and shameful (or rather, shameless) history of aping the Tories on sentencing. No surprise, really: the steepest rise in prisoner numbers occurred under the last Labour Government, as did the fastest ever prison building programme. Indeed, Labour specifically criticised the Government for not increasing sentences enough, for example for rape. Labour is the party of mass incarceration. ‘Tough on crime’, soft on thinking about crime. Instead, Labour focused on identity politics – women, Roma. A historic mistake, in my view, and not just on crime. Yes, minorities are often ill served and need protection. But if that becomes your only selling point, you will never get the nation as a whole behind you and you will never tackle the great radical changes that are needed. Labour has become a party of sectional interests. A word of special shame for Yvette Cooper. She chooses to highlight a rise in police recorded crime since 2015, although she must know that the very bulletin which she took the figure from said that the rise was an apparent one, reflecting improved recording practice; she knows that the same bulletin says that crime survey data is the acknowledged best measure of actual crime, not police statistics; she knows that violent crime is far less frequent today than in the mid-1990s. Yet she chooses to join the Tories in talking up an imaginary crime panic. I used to esteem her, among a lacklustre Labour gallery. Not so much now. It was left to Liz Savile Roberts for Plaid Cymru and Anne McLaughlin for the SNP to oppose further growth in incarceration.. The fine English tradition of opposing mass imprisonment now survives only in the Celtic world. All honour to them. Not that anyone listened. No one listens, nowadays, do they? (1) Katherine M. Auty & Alison Liebling. Justice Quarterly Volume 37, 2020 - Issue 2 6)

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed