|

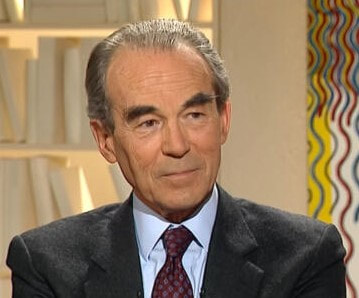

I am reading the memoirs of Robert Badinter, French politician and jurist, Minister of Justice under Mitterand. He is best known for having abolished the death penalty in France (the French were still guillotining people in the 1970s), and campaigning against it worldwide after leaving office: he also secured many other reforms, equalising the age of consent for gays, suppressing some especially repressive laws, improving prison regime, seeking to reduce use of imprisonment and so on. A sort of French Roy Jenkins you might say. Except that Jenkins would hardly have made it his first ministerial act on coming into office to cancel the haute cuisine lunches served daily to the minister, and the daily replacement of flowers throughout the ministry, pointing to the meagre daily allowance for maintaining prisoners in France. Nor I suspect would Jenkins have devoted pages to extolling the merits of his civil servants, ascribing his success to their brilliance. But what is most striking to an English reader, especially today is the passionate belief of the man. Thus: "For the whole of my career in law, I had dreamed that one day it might be given to me to effect a transformation in French justice, to give it a place of eminence in the heart of European liberty. What was a passion for me as a young man under the spell of history, became a sober ambition as university and experience of law brought greater maturity. My conviction was total: the grandeur of France, that phrase that nowadays has almost an antique flavour, and which had nourished me since childhood, could not reside in its military power, now of the second rate, nor its economic power, important though that remained, nor even in the splendour of its culture, overtaken by the dominance of the Anglo Saxons. The grandeur and influence of France for me had to be measured by its contribution to the cause of liberty. It should shine at home with a brilliance without equal, and demonstrate a global influence greater than its actual power. "This vision, which might seem naive, was instilled in me as a child by my father, in the ‘30s, a time when France lived in the glorious memory of the victory of 1918. In Jewish families where one heard that Yiddish accent so sweet to my ears burnt a deep love of the French republic. Then came the black days of defeat, Occupation, Vichy, persecution and deportation. They reinforced my faith in an indivisible alliance between the grandeur of France and liberty. As it became evident that, as the flame of liberty died down or was extinguished, France was plunged into shame or barbarism, I measured all politics by that standard. That principle kept me from supporting communism when I was a student at the Sorbonne, immediately after the war. It caused me to break with governments of the Left which got bogged down in the war in Algeria after 1956. It forbade me to accept the coup d’Etat of May 1958, despite my admiration for General de Gaulle, man of destiny. It made me rally to the small group of friends gathered round Francois Mitterand in the Ligue Pour le Combat Republicain. And later, in the discussion clubs which grew up among the non communist Left in the 70s, my subject for study and discussion was always the same: what should French liberty be like at the end of the 20th century?" When one thinks of the pitiable succession of mediocrities who have shambled through the offices of Lord Chancellor and Home Secretary in recent decades, each replaced and forgotten within a year or two, each leaving a little more mess behind them (1), it is inconceivable to imagine of any of them harbouring such elevated thoughts. And so degraded is our political culture that if any of them had said something like this, it would have simply been assumed that they were suffering from an unusual form of mental breakdown. But he was not a dreamer. Badinter was - or rather is, happily alive and engaged still in his 90s - that rarest thing in politics, an idealist who got things done. As we say: a mensch. (1) Or Grayling's case, a vast mess

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

I was formerly Finance Director of the Prison Service and then Director of the National Offender Management Service responsible for competition. I also worked in the NHS and an IT company. I later worked for two outsourcing companies.

Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

Click below to receive regular updates

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed